Library member Kensa Broadhurst is studying at Exeter University, and has been using Morrab Library’s extensive archive collections for her research since we re-opened. She came across two fascinating documents, written by prisoners of war. The library holds facsimiles of their diaries. Here’s Kensa’s take on them….

I have been working my way gradually through the archives at the Morrab Library whilst researching for my PhD. The letters, journals and notebooks held in the Morrab archives are a real window into the past and offer a fascinating view of not only daily life, but contemporary views on the wider world too.

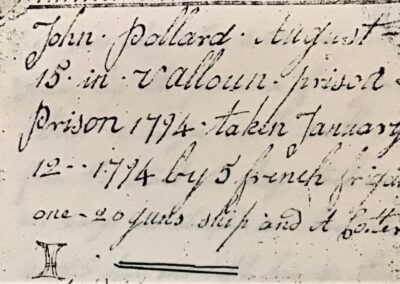

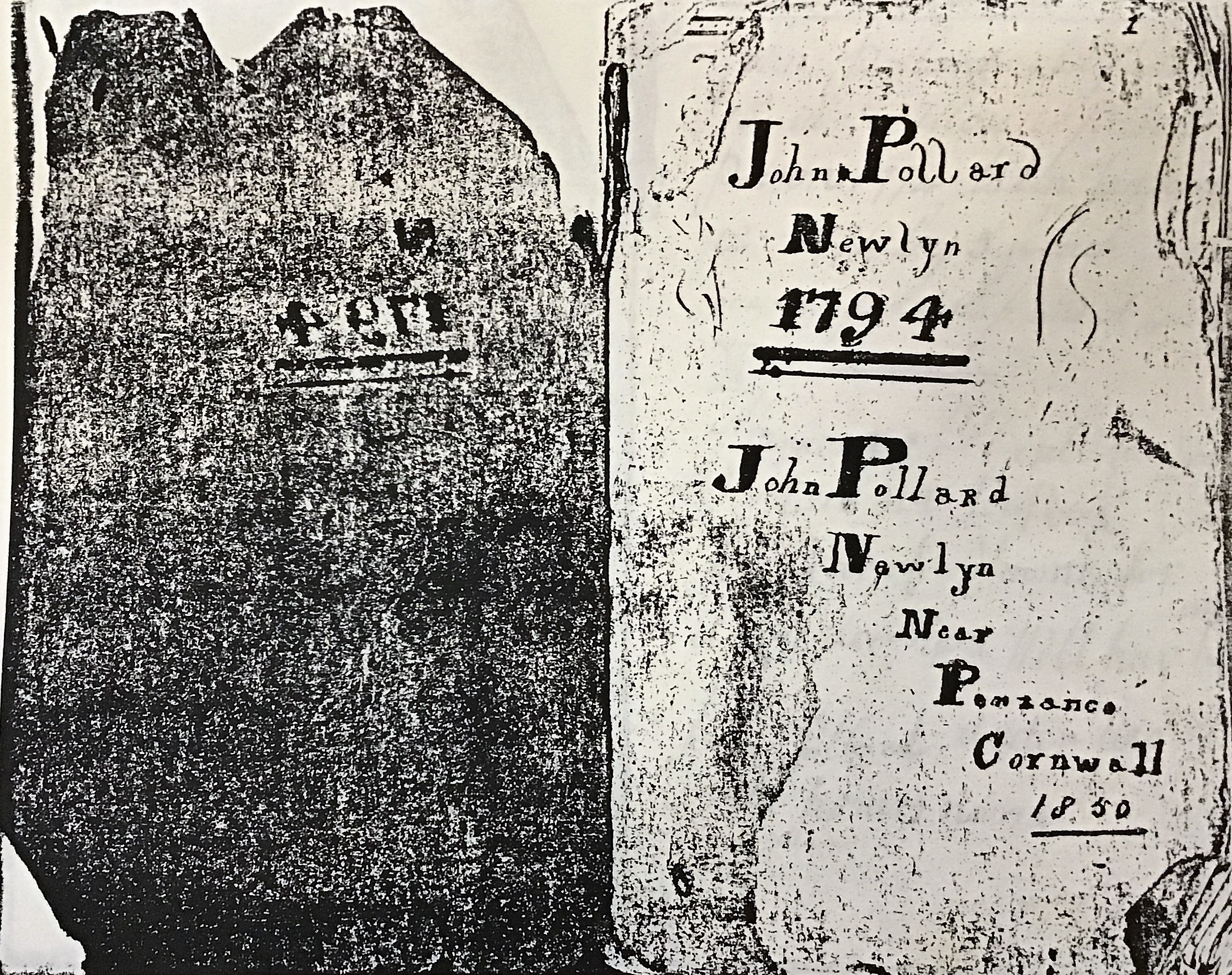

Two of the most interesting documents I have read recently concern Revolutionary France and the Napoleonic Wars. John Pollard, a ship’s Captain from Newlyn, was a prisoner of war in France from 1794-95 who kept a journal for a large portion of his time in captivity. Similarly, Captain James Quick was held captive from 1810-14. He wrote a series of letters to his wife in St Mawes detailing his life as a prisoner.

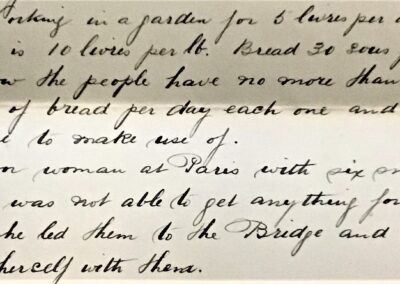

Pollard tells us that he began to write his journal only after several months of captivity and so it is unclear whether his account of this early time is copied from elsewhere or based on memory. Pollard’s account not only details the trials, tribulations and practicalities of life as a prisoner of war, but offers a contemporary view of wider events in Revolutionary France. Some of these are hearsay, or titbits of news picked up sometimes long after the events in questions, such as the death of Louis XVII, or the results of Naval Battles, but through Pollard’s journal we are also able to track the effects of inflation and food shortages on France at this time. The price of bread steadily increases from 1 to 15 livres per pound for example. I found it fascinating to discover that whilst the prisoners were given a certain food allowance each day, Pollard was also able to work and earn money. Although there were times when he was unable to work due to illness, the weather or changes in regulations within the prisons in which he was held, at various times Pollard works as a gardener, builds roads, repairs fishing nets, heaves rubbish and works in a grocers, variously grinding pepper and coffee. We also hear of other prisoners getting drunk in the local public house, starting a fight and breaking things! Pollard also keeps track of the escapes, and attempts, of other prisoners. Some of these are more successful than others.

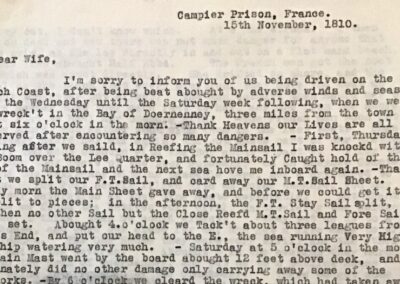

As Quick’s letters were written with an intended recipient in mind, his wife, they chart a wider range of emotions than Pollard’s journal. We sense his frustration in the early letters when Quick has evidently not received any letters himself, then relief that he does finally hear from his wife, coupled with annoyance that his brothers do not think to write to him. The letters also discuss the practicalities of receiving post (via the Transport Board seem to be the most reliable means), and the frustrations of not being a regarded a Prisoner of War by the Committee for Prisoners of War at Lloyds of London (and therefore able to claim money for support) as he had been shipwrecked on the French coast and then imprisoned. The French view was that all were regarded as prisoners of war, whether shipwrecked, captured or forced to seek shelter in a French port by adverse weather. Lloyds evidently wanted to avoid paying out any money! Quick’s letters also give us an insight into contemporary networks within Cornwall. In his letters he lists other Cornishmen with whom he is held captive and their hometowns in order that his wife and get word to their families of their situation. As well as men from Mevagissey we hear of several men from St Ives. We learn Quick spent his time in captivity learning French and some of the language begins to find its way into his writing.

Examining documents from the past not only makes me realise how privileged we are to have a wealth of archives, such as those held at the Morrab, but also make me feel more connected to the past. As I drive around Penzance and the local area, places which feature in the documents I have read now jump out at me as I think about the people who lived there and the events which took place which I have discovered.