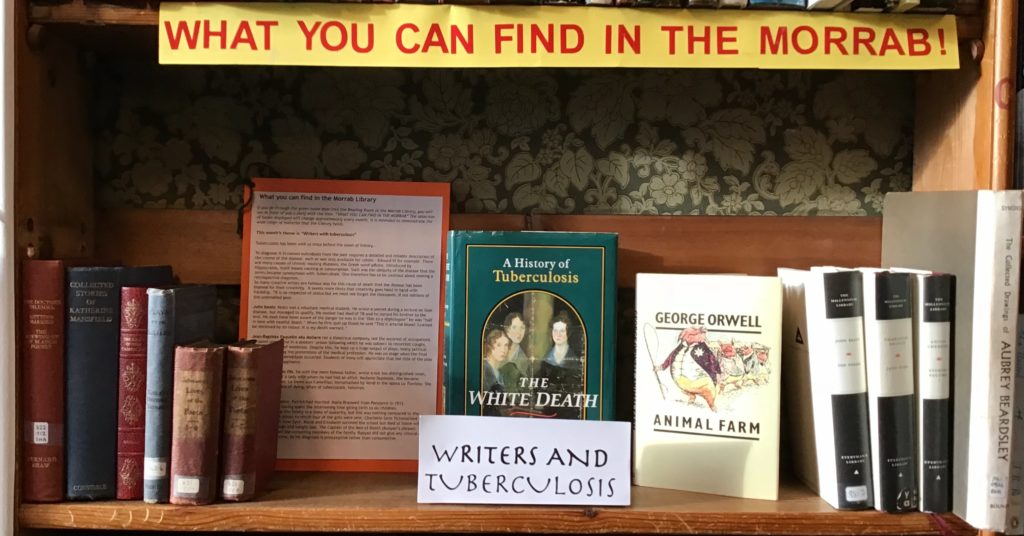

If you go through the green baize door into the Reading Room at the Morrab Library, you will see in front of you a shelf with the title “WHAT YOU CAN FIND IN THE MORRAB” The selection of books displayed will change approximately every month. It is intended to demonstrate the wide range of material that the Library holds.

This month’s theme is “Writers with tuberculosis”

Tuberculosis has been with us since before the dawn of history.To diagnose it in named individuals from the past requires a detailed and reliable description of the course of the disease, such as was only available for celebs – Edward VI for example. There are many causes of chronic wasting diseases; the Greek word φθισισ, introduced by Hippocrates, itself means wasting or consumption. Such was the ubiquity of the disease that the terms became synonymous with tuberculosis. One therefore has to be cautious about making a retrospective diagnosis.

So many creative artists are famous also for this cause of death that the disease has been blamed for their creativity. It seems more likely that creativity goes hand in hand with hardship. TB is no respecter of status but we must not forget the thousands, if not millions of the unannalled poor.

John Keats: Keats was a reluctant medical student. He wrote a sonnet during a lecture on liver disease, but managed to qualify. His mother had died of TB and he nursed his brother to the end. He must have been aware of the danger he was in the ‘Ode to a Nightingale” he was “half in love with easeful death.” When he first spat up blood he said “This is arterial blood: I cannot be deceived by its colour. It is my death warrant.”

Jean-Baptiste Paquelin aka Moliere ran a theatrical company, not the securest of occupations. He spent some time in a debtors’ prison following which he was subject to recurrent coughs, fevers and bouts of weakness. Despite this, he kept up a huge output of plays, many satirical and many mocking the pretensions of the medical profession. He was on stage when the final fatal attack of haemoptysis occurred. Students of irony will appreciate that the title of the play was Le Malade Imaginaire.

Alexander Dum as fils, he with the more famous father, wrote a not too distinguished novel, then a play about a lady with whom he had had an affair, Madame Duplessis. She became Marguerite Gautier, La Dame aux Camellias; immortalised by Verdi in the opera La Traviata. She is one of a long line of dying, often of tuberculosis, heroines.

The Brontes: Father, Patrick had married Maria Branwell from Penzance in 1812. She died in 1821 having spent the intervening time giving birth to six children. Father brought up the family in a state of austerity, but this was nothing compared to the conditions at the school to which four of the girls were sent. Charlotte later fictionalised it as Lowood School in Jane Eyre. Maria and Elizabeth survived the school but died at home within the year with cough and weight loss. The Captain of the Men of Death (Bunyan’s phrase) eventually took all the remaining members of the family. Bunyan did not give any clinical details of Mr Bronte’s illness, so his diagnosis is presumptive rather than consumptive.

Anton Chekov was yet another tuberculous doctor, but one who continued to practise his profession despite his illness. He qualified in medicine in 1884, in which year he had his first haemoptysis (the coughing up of blood). He must have known he was affected, but refused to have himself “sounded”. His first foray into drama was “Ivanov”, the only one of his plays to make specific reference to tuberculosis. By the time The Seagull was produced he was forced to accept the situation and moved south to Yalta. His version of an easeful death was to exclaim “I’m dying”, whereupon his doctor gave him a glass of Champagne. He had time to say “It’s a long time since I had Champagne” before slipping quietly away. Cue romantic music and curtain.

The hero of George Bernard Shaw’s novel The Doctor’s Dilemma is one Dubedat, a dying artist. The whole play centres around tuberculosis and its possible cure and there are thinly disguised portraits of the senior medical figures involved in what was a very real controversy at the time. Dubedat is an equally thinly disguised version of Aubrey Beardsley who died from TB in France at the age of 25.

Katherine Mansfield , famous as a short story writer noticed the first signs of illness when she was on holiday in Cornwall. Her letters and journals show how much she dreaded the disease. She went on to try every remedy she could find (including X Ray treatment to the spleen), dying finally in a quack clinic in France.

George Orwell was unlucky. It was possibly during his self imposed hardship as a down and out that he first contracted the disease. He lived into the antibiotic era, although only just. His streptomycin was obtained from the USA with a nudge from Nye Bevan himself, but he developed a severe sensitivity to the drug and was forced to discontinue. Had he been treated only a little later this complication could perhaps have been dealt with.

Dr Samuel Johnson: An exception to this lugubrious catalogue of death, Dr Johnson did not die of TB, but he suffered from Scrofula, tuberculous glands in the neck and was “touched” by Queen Anne. For centuries patients were given the ‘Royal Touch’. The monarch’s hand on the head, a blessing and a small coin (a specially minted ‘touch piece’) constituted the ceremony. Not all participants believed in what they were doing, William III’s response was “God give you better health and better sense”, but a bit of gold is always welcome.

I cannot complete this blog without paying tribute to Dr Thomas Dormandy from whose book ‘The White Death’ much of this information comes.

Martin Crosfill, Honorary Librarian