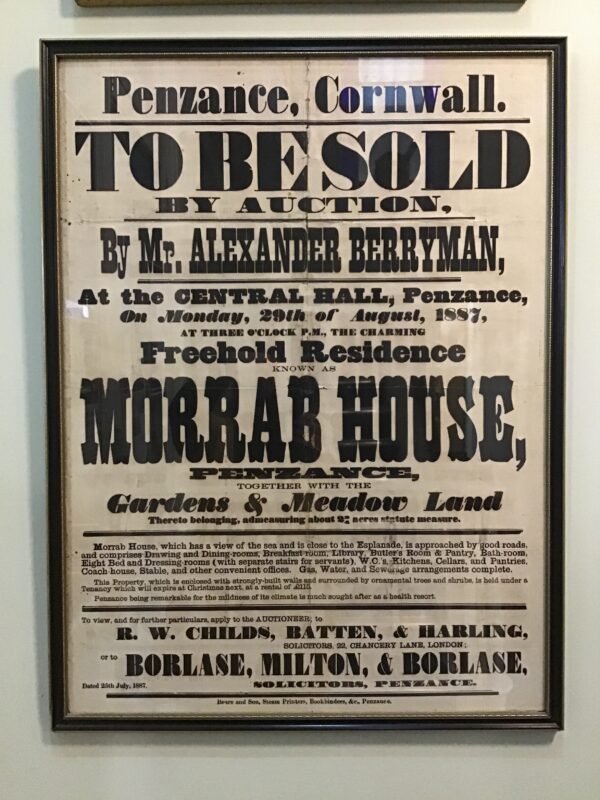

Among the many fascinating items displayed inside the Morrab Library is a bill of sale dated 1887, detailing the accommodation offered at Morrab House. Some of the rooms and stairways are easy to identify, some not, and there seems to have been a certain amount of double counting with regard to bed and dressing rooms… but hey, that’s the property business.

This was the building and land that would later be purchased by Penzance Town Council, keen to establish a garden for the pleasure of residents and the better class of tourist – and in the process acquiring the house, more or less by accident.

The original owner, Samuel Pidwell, had been a notable man. Educated at Oxford, in his youth he had made an early ascent – the 17th – of Mont Blanc. Back in Penzance, he married his cousin Ann Batten. The couple, two children (four more would follow later), Ann’s sister and four servants built themselves a brand new house in Morrab Fields, with a clear view out into the Bay and westwards to Penlee Point. Samuel Pidwell, although describing himself as a brewer, had considerable investments in mining. Before his death in 1854, aged only 46, he served twice as mayor, and was prominent in the Royal Geological Society of Cornwall.

Later, the house was owned by Charles Ross. 150 years on, he is known principally for the bridge that still bears his name, and his supporters would point to the development of Morrab Road as further evidence of his goodwill and forward thinking. But in his own time, Charles Ross had other claims to fame: as the developer of Newlyn harbour, thereafter as the Conservative MP for St Ives constituency, and finally – in 1896 – for misjudgements that led to the spectacular collapse of the Batten, Carne and Carne Bank.

And so the Corporation acquired – at a cost of £3,120 – a fine building and surrounding land. The Town Council enthusiastically set about developing the grounds, but decided that the house should be leased out. The YMCA – at this date, identified with education and the promotion of wholesome living rather than housing provision – was the only formal bidder. “It is hardly likely that a better tenant will come forward,” the Cornish Telegraph suggested, while acknowledging that the Penzance Library – then housed in the Public Buildings, now St John’s Hall – might still be on the lookout for a new home. “We shall see,” the newspaper added darkly, “what we shall see.” Sure enough, a bid from the Library arrived in due course, and although their offer was almost identical to the YMCA’s, it was the Library’s bid that was accepted.

Not everyone, however, was happy with the decision. There were objections about carriages driving through the Gardens (YMCA clients would presumably have arrived on foot or bicycle), and the perceived exclusiveness of the Library. A letter to the Cornish Telegraph later referred to “the ‘class’ legislation which installed a lot of wealthy people in Morrab House.

The Library moved to its new premises in August 1889. The Cornishman reported that “a number of members seemed unwilling to say goodbye” to the old St John’s Hall rooms, and “lingered an hour after closing time.” Anxiety about fire from theatrical shows had prompted their move, and this was not left entirely behind. On the fine September evening when an evening illumination provided a finale for the official opening of the new Gardens, Morrab House remained “shrouded in darkness, the one dismal spot” on account of the Library staff, and “that haunting dread which has driven them from their old home [and] seems to hang over them still.”

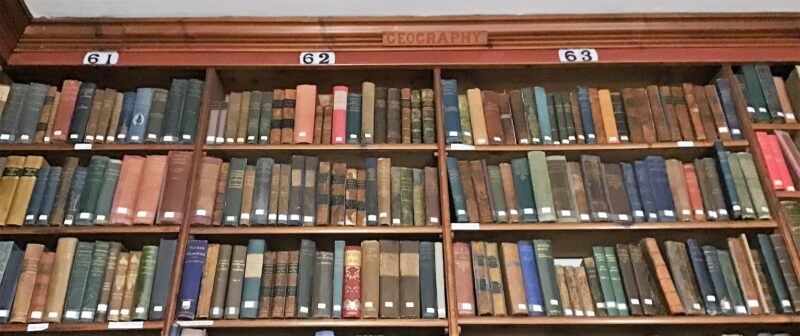

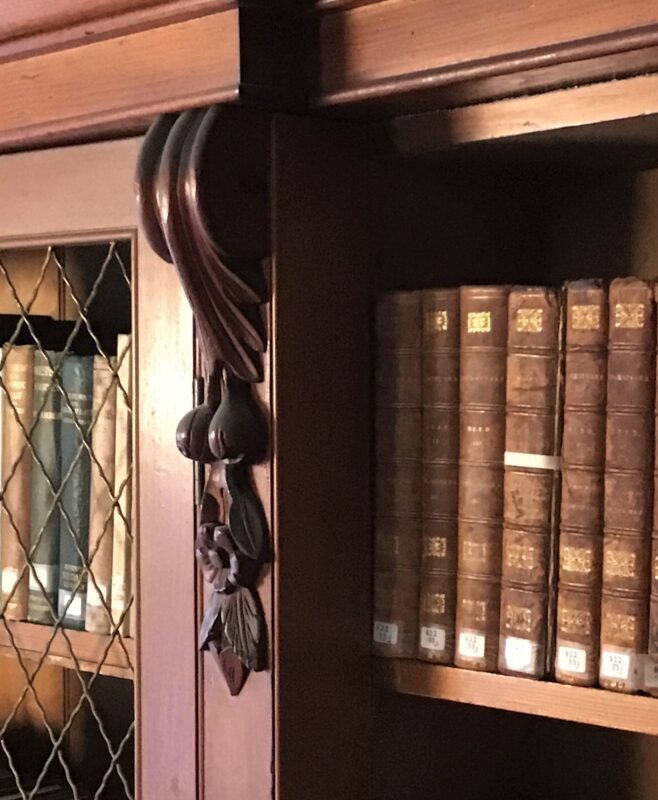

Despite this gloom, floor to ceiling shelves were constructed in most of the rooms. Most of these survive today, as do many of the original fittings throughout the house. You can still glimpse some of the Pidwell’s wallpaper on the walls behind the shelves, admire the marble fireplaces and the rose cornices on the ceiling, and still feel as though you are sitting in a beautiful family home.

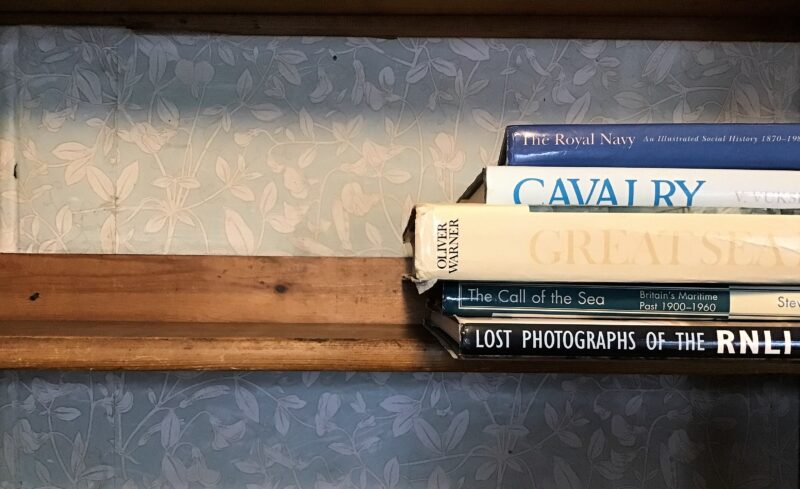

But the real problem at the spacious new premises in 1889 was that the rooms had to be filled. William Bolitho of Ponsandane came forward with a substantial bequest, to be spent on books costing at least two guineas each. Other major bequests and donations followed, perhaps the most significant donor – certainly in terms of volume – being the 1911 bequest of Prebendary Philip Hedgeland, Vicar of St Mary’s Church. Pick books from the shelves in any room – science, literature, classical or modern languages – and you are likely to find that they once belonged to him.

Since then, the Library has certainly had no problem filling its shelves – and although various changes have been made to the building, the original parts remain very much the same as they were in 1889. Lights and other fittings have been updated as times have changed, carpets have been laid (and taken back up again to reveal the wooden floors), wallpaper has been pasted on (and painted over) – and the books have migrated from shelf to shelf and from room to room; but Morrab Library’s quintessential essence remains. Even the major extension to the building in 2013, now housing our art room and Photographic Archive, served to only enhance this remarkable space: Samuel Pidwell’s Morrab House of 1841.

Perhaps the best way to end this blog is to quote the quintessential local author Arthur Quiller Couch:

‘There are hundreds of bigger and finer libraries, but few have a pleasanter tradition, and not one is so beautifully placed. Can a bookish man imagine anything more delightful than a library put together by the taste and care of generations of scholars and students, and set in a garden?’

We think not, Q; …we think not.

Linda Camidge

December 2021