Blog

Conrad Gesner – fantastic creatures and ancient books

Humans have been drawing what they see of the natural world for over 40,00 years. Initially capturing images on rocks and in caves, this evolved over many centuries into hand drawn depictions and written descriptions being recorded in manuscripts. The development of the printing press in the 15th century changed everything – it was the first time mass produced books, complete with images, could be disseminated to a far wider audience than ever before. This, alongside developments in shipbuilding which allowed further travels afar, generated enormous interest and a huge demand for knowledge about the natural world beyond people’s own geography.

This period heralded the time that the science of natural history emerged, when many naturalists tried to make sense of the world, studying, collecting and classifying species and publishing compendiums and encyclopedias. This was also still a time when people accepted myths, legends and monsters as reality, so it was not unusual to believe in both science and the existence of dragons and unicorns.

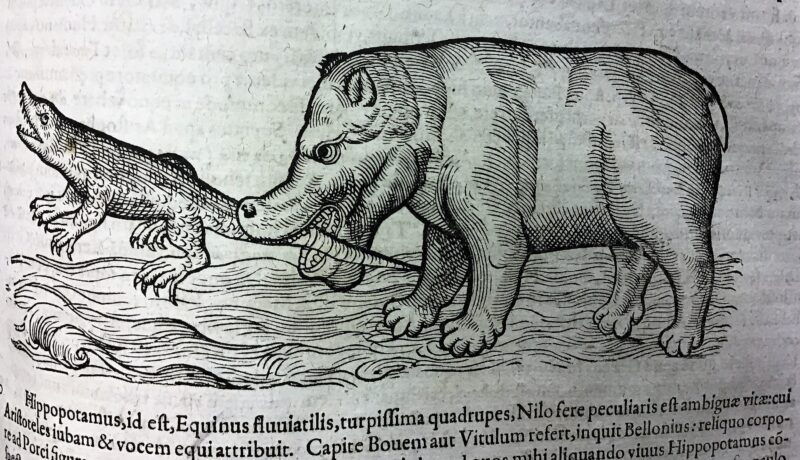

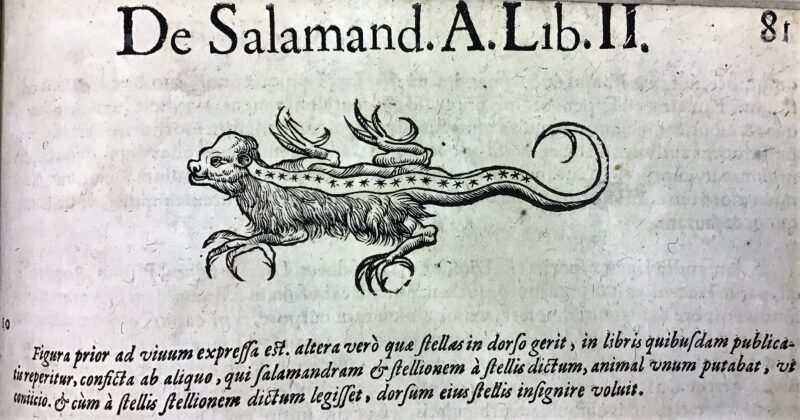

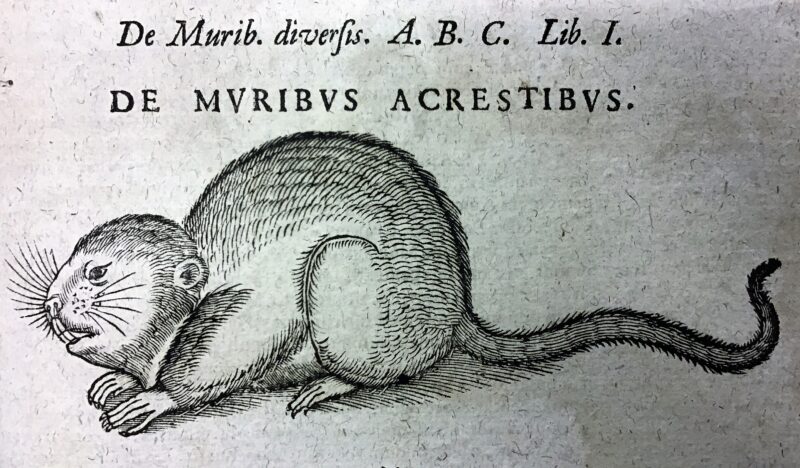

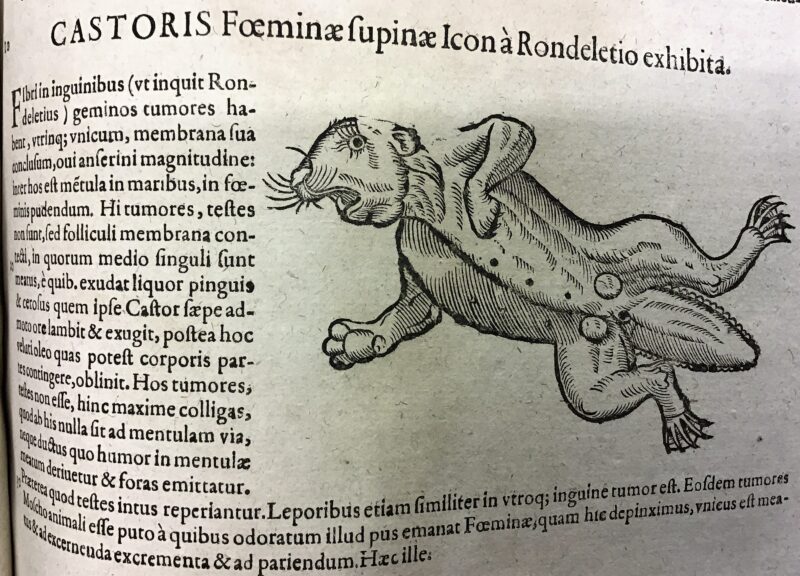

Many published naturalists at this time didn’t travel far. Instead they relied on (sometimes distorted) descriptions of animals that fellow travellers and explorers had seen in order to create an image. As a result, depictions of animals weren’t always entirely accurate, and mythical creatures such as satyrs, hydras and sea monsters were often to be found depicted in the pages between horses and geese. They couldn’t prove that the creatures described didn’t exist, and there was no David Attenborough on hand to tell anyone otherwise, so everything was included. For example, many sailors told of amazing sea creatures and mermaids on their journeys, but it must be remembered that fresh water wasn’t available and rum was the drink of choice onboard! They may well have just been exaggerations of quite normal, or now extinct, sea creatures.

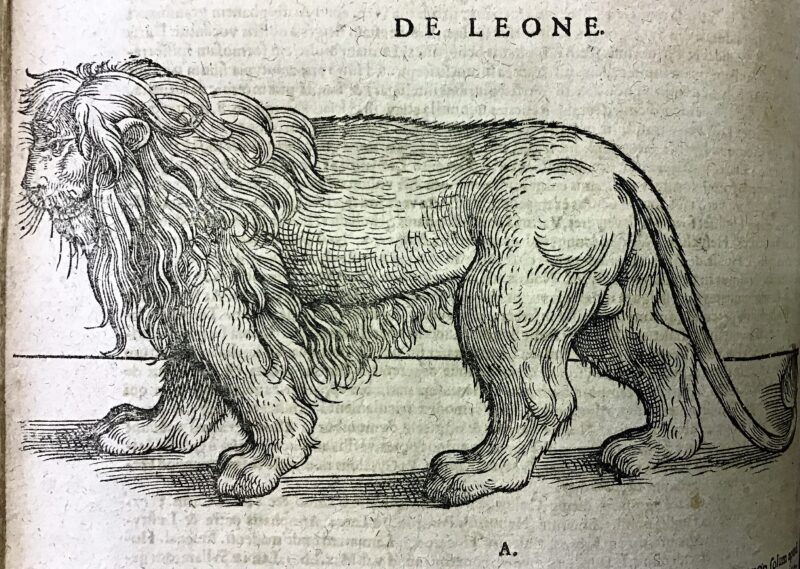

One of the earliest published naturalists was Conrad Gesner. A Swiss national who rarely travelled far and who died from the plague at the age of 49, he published widely on a number of subjects. His magnum opus however was the five volume Historia Animalium (1551-1558), comprising more than 4,500 pages of images and descriptions of all known creatures at that time. He combined information from his research of historic sources, such as the Old Testament, Aristotle and Pliny, as well as folklore and medieval bestiaries, with his own observations to create the first comprehensive description of the animal kingdom. Historia Animalium was also one of the first books to be illustrated with woodcuts drawn from personal observations by Gesner and descriptions from his colleagues. It was published in the two recognised scientific languages of the day – Latin and Greek.

The book wasn’t without its controversy. Pope Paul IV added Historia Animalium to the Catholic Church’s list of prohibited books. Gesner was a Protestant and the Pope felt that his faith contaminated his observations and writings.

The legacy of Gesner and other naturalists of his time cannot be underestimated. They were the people who established the basis of the science of zoology, classification and taxonomy – the first to try to categorise like groups of species together. Their drawing style and technique still influence the way scientific illustration is presented today. And the volumes provide an important snapshot into society’s knowledge, and beliefs of that time, where mythology and science were beginning to disconnect.

Morrab Library is fortunate to hold the first two of the five volumes of Historia Animalium in its collections. Our editions are dated 1617-1620, around 70 years after they were first published, and they are a very special treasure amongst our collections.

Lisa Di Tommaso, Librarian

Women Writers and Georgian Cornwall – by Charlotte MacKenzie

Library member and writer, Charlotte MacKenzie, has written this short piece about her latest book –

Mary Wollstonecraft’s youngest sister Everina was appointed in 1797 as governess to the family of the second Josiah Wedgwood. The events which followed affected the lives of five women writers three of whom had close family associations with Cornwall. In February Everina stayed with Mary in London before travelling to the Wedgwoods. During her visit Everina went out for the day with a friend, the poet Anne Batten Cristall who had been born in Penzance.

Mary was three months pregnant and married William Godwin in March. After Mary gave birth to her second daughter the placenta failed to deliver. The novelist Eliza Fenwick, who was the daughter of a Methodist itinerant preacher from Newlyn, nursed Mary. Godwin then asked Eliza to write to Everina with the news that Mary had died. Everina made plans with her sister Eliza Bishop to adopt Mary’s two daughters. After visiting her sister in Ireland Everina did not return to the Wedgwoods. Fanny Imlay and Mary Godwin, the future author of Frankenstein, continued to live with William Godwin.

In October the Wedgwoods arrived at Mount’s bay in Cornwall where they had taken a house for the winter and their daughter Charlotte was born. By the spring the Wedgwoods were searching for a new governess. They appointed Thomasin Dennis who later wrote and published a gothic novel while she was living at Trembath near Penzance.

Fifteen years later the families of a Cornish Admiral’s widow and a banker who was a widower were part of the same social circle in Truro. These families included at least four female members who later published novels or verses. Two of the banker’s daughters, Charlotte Champion Pascoe and Jane Louisa Willyams, published a novel together in 1818 after Walter Scott sent their manuscript to his publisher. Louisa and Charlotte both later separately published their individual writing.

The Michell family had returned to Truro after living in Portugal. Charlotte’s friend Anna Maria Michell, whose married surname was Wood, published verses in magazines and in 1838 printed a volume of verse including some of her translations from Portuguese and Italian. The youngest and most prolific writer was Emma Caroline Michell, who had been born at Lisbon, and who many years later started to write when aged in her 60s and published thirteen sensation novels which were mostly set in Cornwall; initially using the pseudonym ‘C. Sylvester’ and later in her own married name Lady Wood. She also published a volume of verses with her daughter Anna Caroline Steele who was a writer; as was another of her daughters Emma Barrett-Lennard who was also a composer who set songs to music.

When I discovered the writing of these women and others like them who had strong associations with Cornwall, I wanted to tell their life stories. Women writers and Georgian Cornwall (2020) is available from online retailers as a paperback or EPUB. Readers are welcome to contact me charlottemackenzie1@gmail.com

You can watch Charlotte’s online talk for Kresen Kernow here.

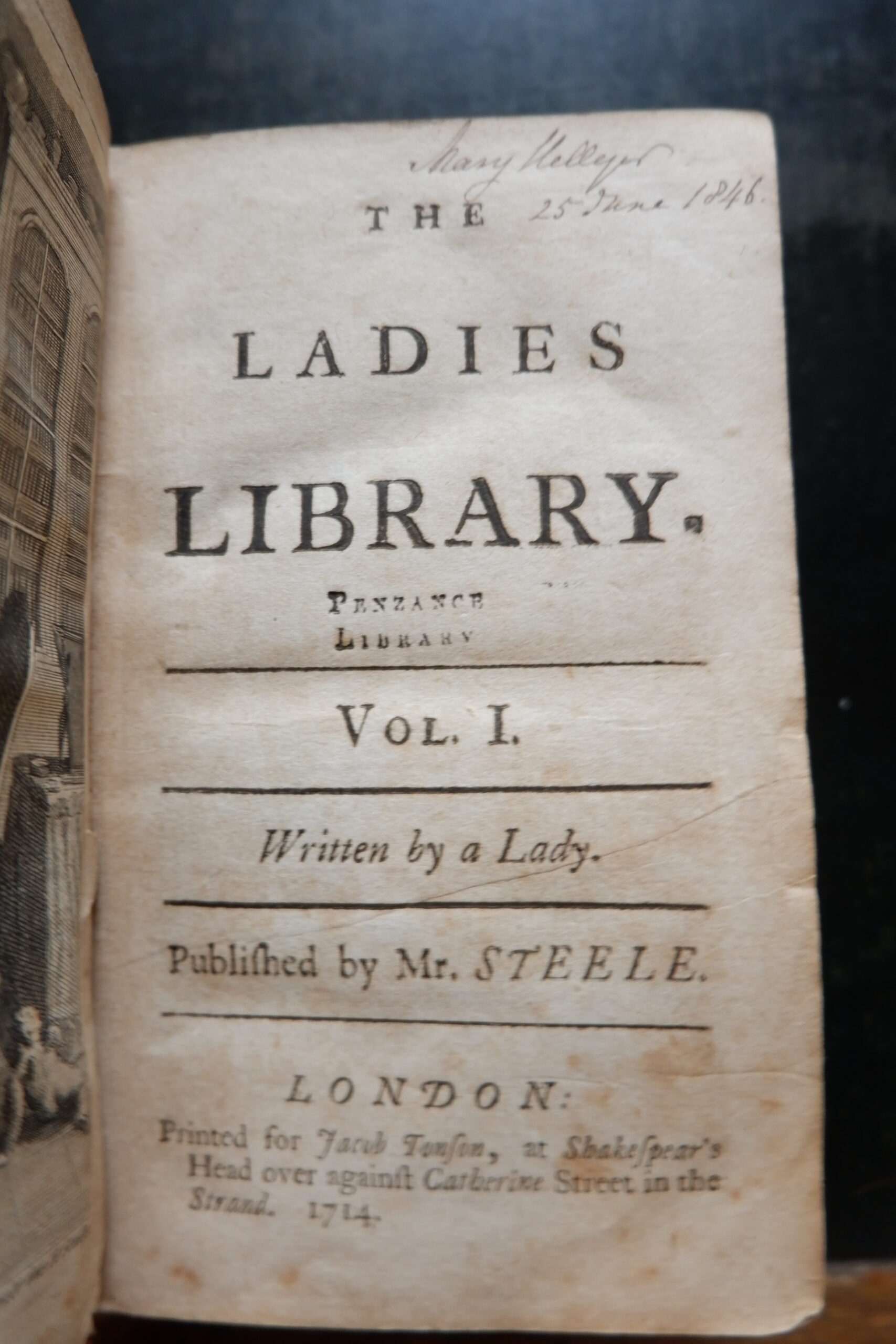

The Ladies’ Library

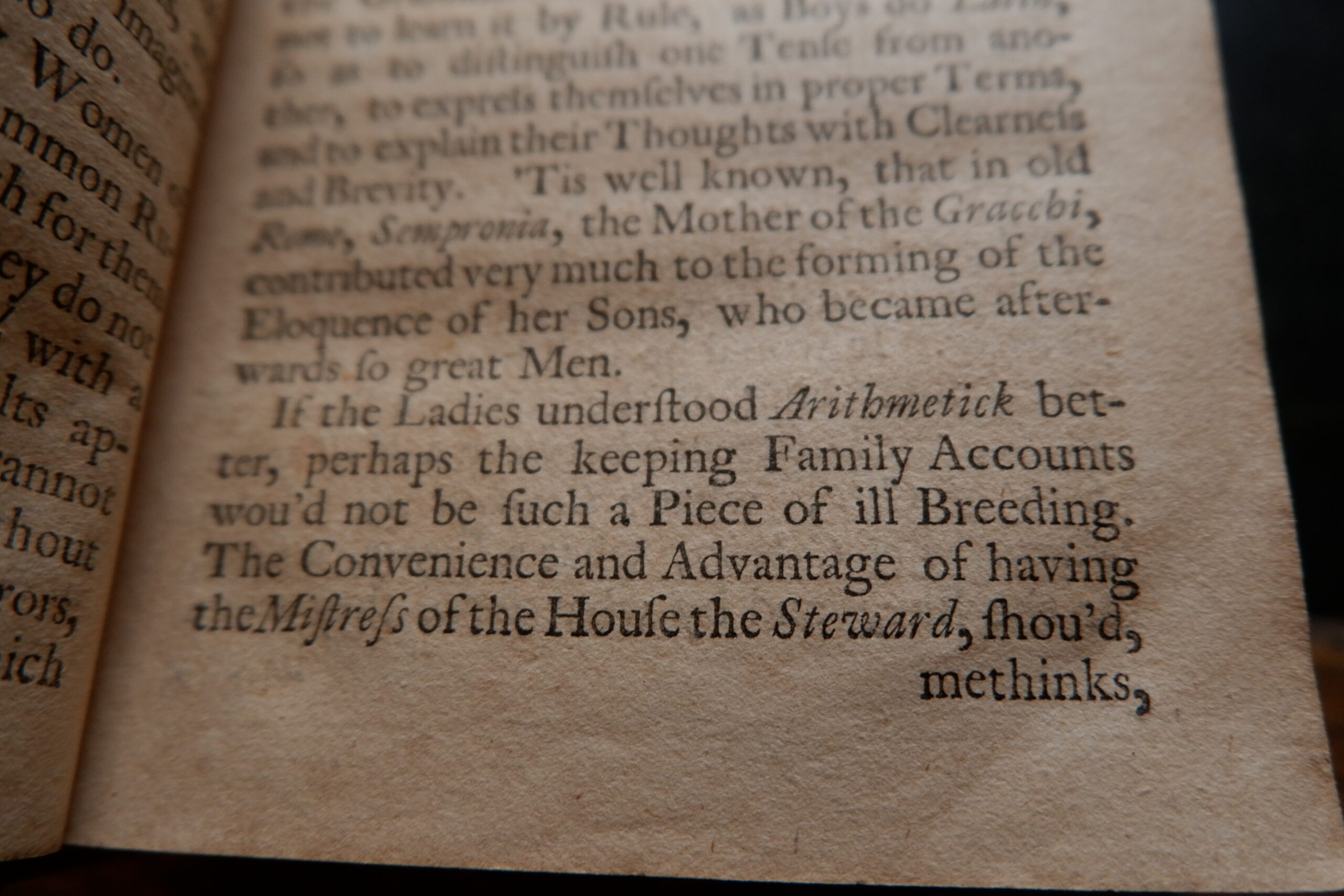

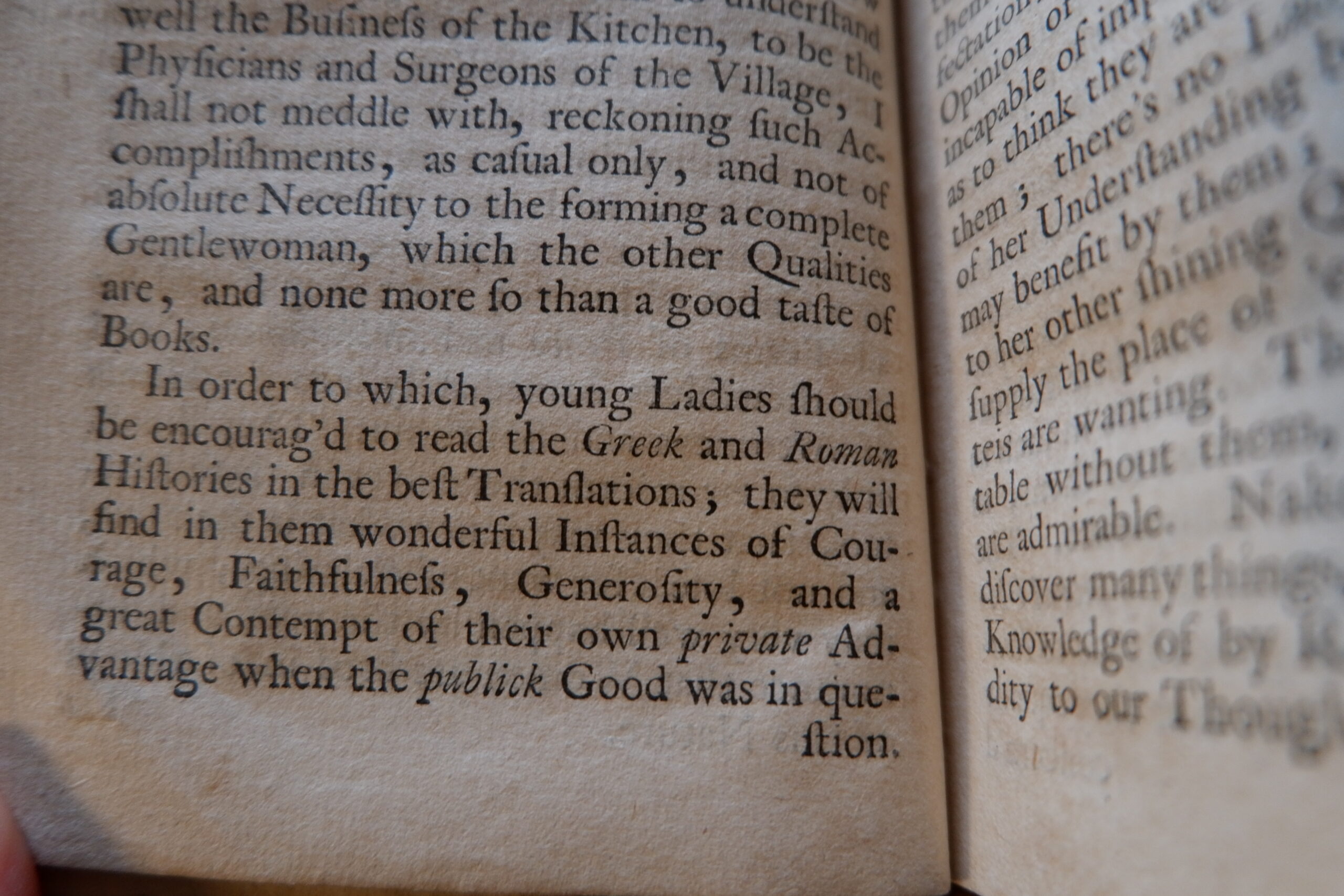

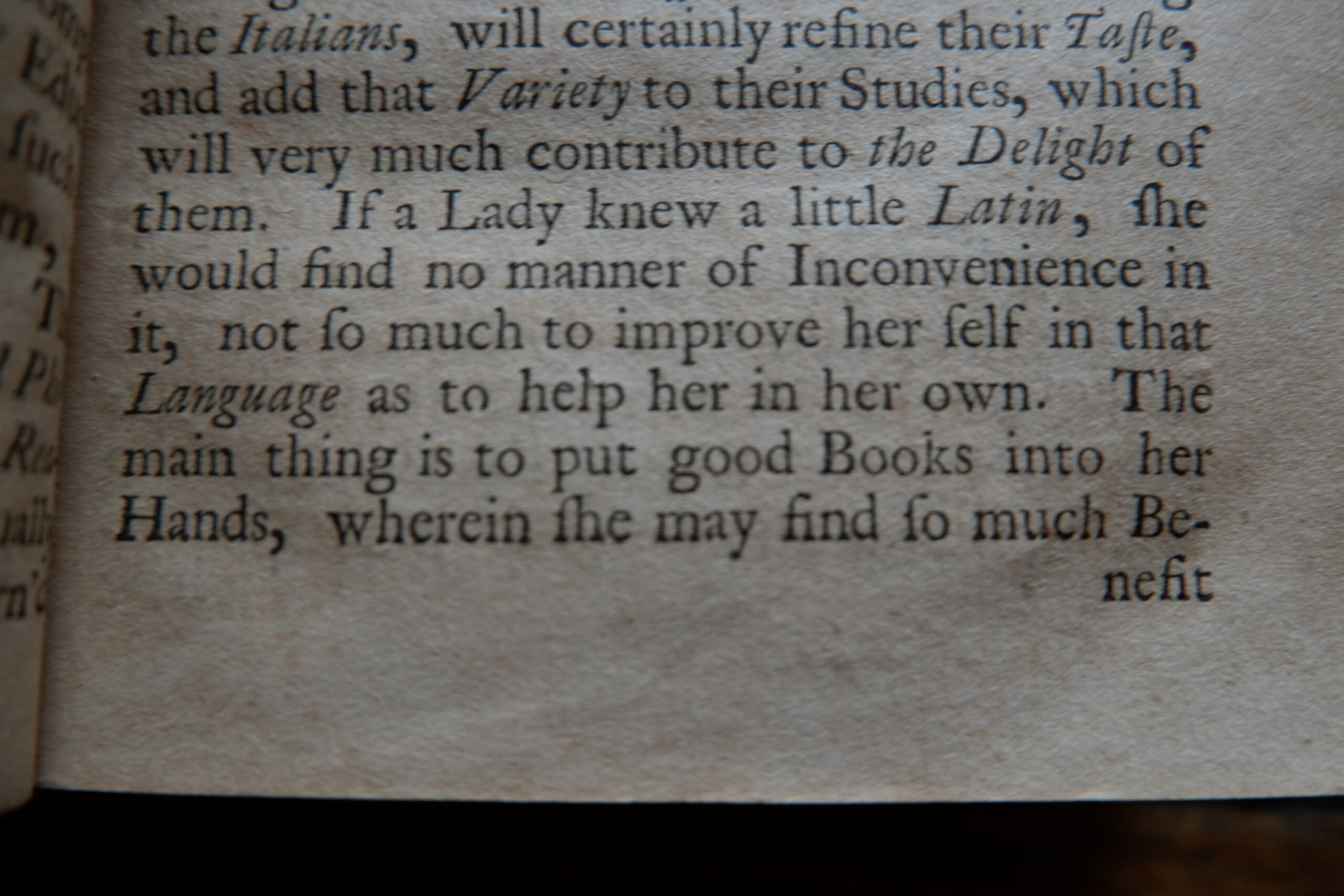

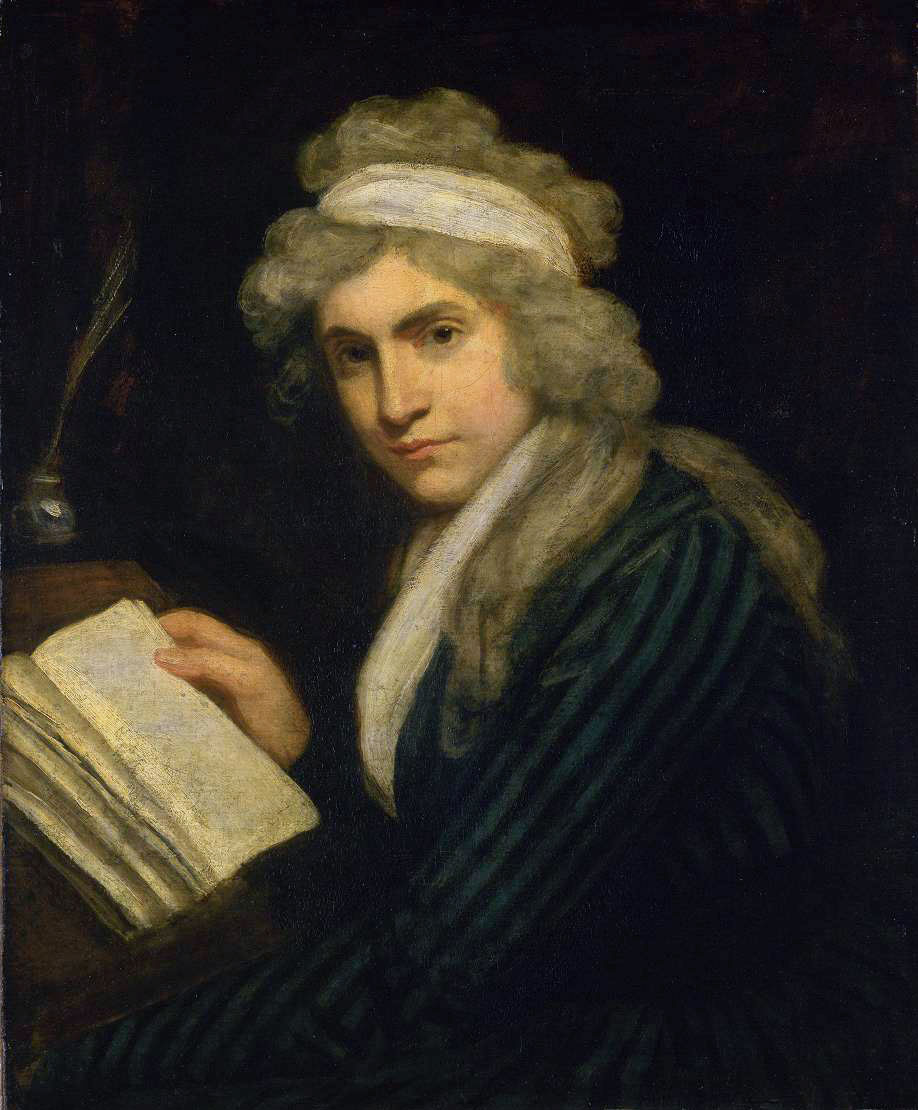

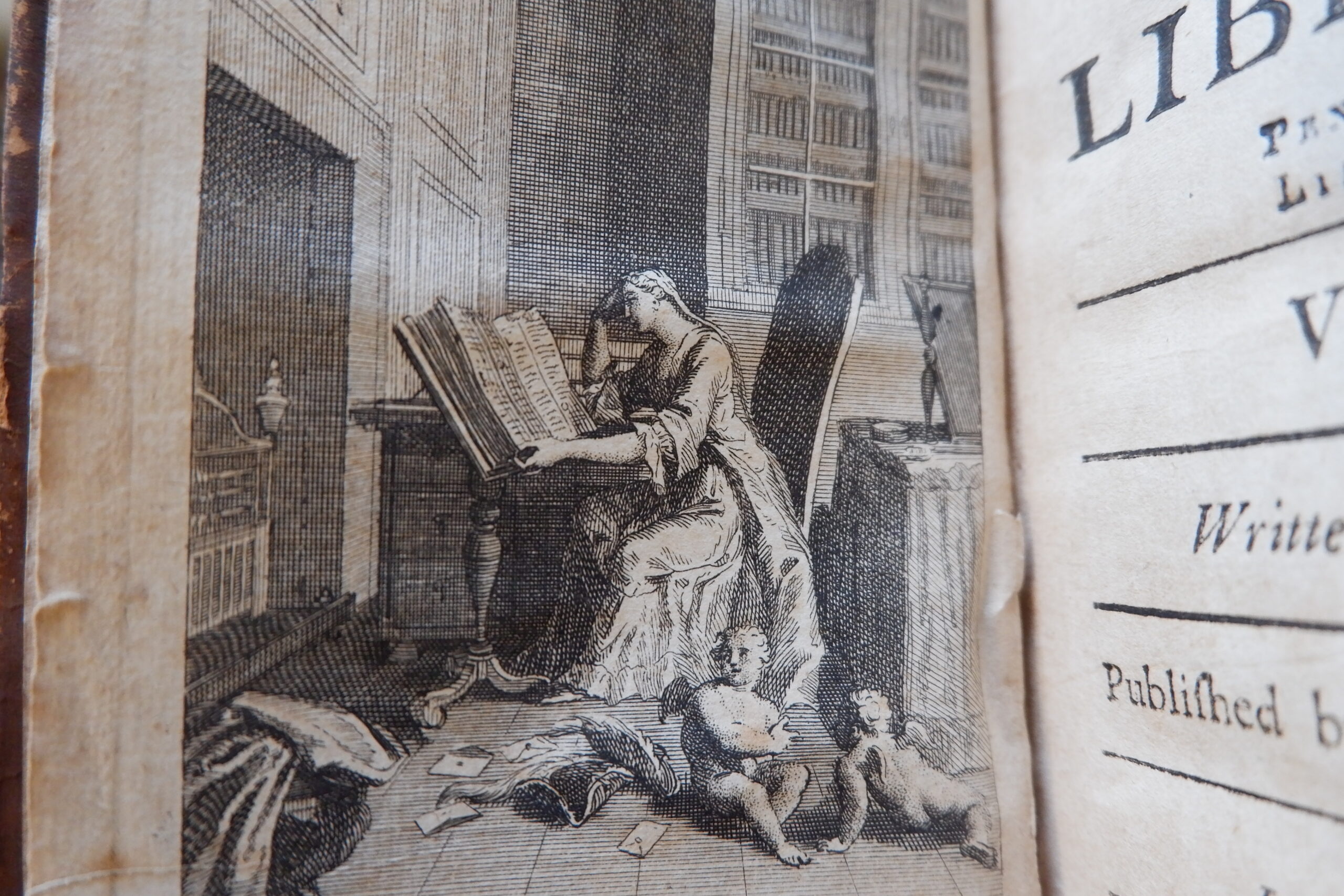

When looking for something to post for Women’s Day this year we thought we’d have a browse through some of our older, rarer books – and we stumbled upon this gem – The Ladies’ Library, in 3 volumes, 1716 – written by ‘a Lady’ (attributed to Lady Mary Wray.) We felt sure we were the target audience for this. So, we sat down, in the best spot in the library (with a clear view of the sea) and began reading volume one – looking rather like the lady in the frontispiece (we, too, have a few cherubs scattered around.)

The Ladies’ Library turned out to be a kind of ‘how-to’ guide on being a proper, well-bred, and devout Christian lady – with chapters including instruction on ‘Wit and Delicacy’, ‘Dress’ and ‘Meekness’. (We won’t lie, we’re often in dire need of instruction on all those things – though our confidence in being the target audience was beginning to waver.)

Its author is clearly a product of her time (that ubiquitous defence of historical works) – of its stifling gender prescriptions. And her need to be desirable, and to conform to a purely patriarchal model of woman, is palpable. There are countless encouragements to be modest, deferential, and chaste. Along with constant references to the weaker sex (her italics). But we can’t help feeling some of this is a placation, a version of prefacing something insightful with ‘of course, I know nothing about this, but’ – something women often learn to do, in having to ask permission to speak.

“A young lady should never speak, but for necessity, and even then with diffidence and deference” but nonetheless this lady does speak, very eloquently, and some of the things she has to say are surprising. We were particularly taken with the first chapter on ’employment’ where she urges women not to be idle, and to educate themselves beyond the traditionally ‘feminine’ subjects – to learn arithmetic, law, and even latin. She’s especially fond of history – and of reading in general which she assures will give “solidity to our thoughts, sweetness to our discourse” – we couldn’t agree more!

The chapter on ‘dress’ is lengthy and very much informed by Christian and patriarchal ideologies (not entirely separate.) It can largely be summarised as ‘cover yourself up ladies!’ or risk seduction, sin and eternal damnation (well, that told us.) But she particularly emphasises just how much time women waste on the “dressing up box”, on making oneself attractive for men, when there are far more productive things one could be doing – we suspect Naomi Wolf, in The Beauty Myth, would agree.

At this point, the cherubs started to get restless and we’ve had to take a break to placate them – though we look forward to delving into volume two in future. The Ladies’ Library is by no means a feminist work but reading it has reminded us of the complexity – and suppression – of women’s voices in history, and the absolute importance of listening to them. It’s with a sigh of relief, too, that we write this – educated, indelicate, bold, wearing what we like, saying what we like, and working for a library absolutely full of exceptionally brilliant women (staff, volunteers and members.) We feel immense gratitude to the incredible women, and the feminist movements, that have made that possible – and reflect on the work still to be done.