Humans have been drawing what they see of the natural world for over 40,00 years. Initially capturing images on rocks and in caves, this evolved over many centuries into hand drawn depictions and written descriptions being recorded in manuscripts. The development of the printing press in the 15th century changed everything – it was the first time mass produced books, complete with images, could be disseminated to a far wider audience than ever before. This, alongside developments in shipbuilding which allowed further travels afar, generated enormous interest and a huge demand for knowledge about the natural world beyond people’s own geography.

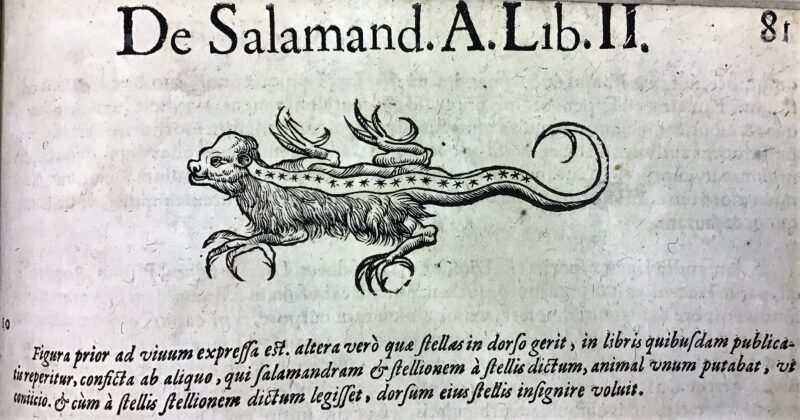

This period heralded the time that the science of natural history emerged, when many naturalists tried to make sense of the world, studying, collecting and classifying species and publishing compendiums and encyclopedias. This was also still a time when people accepted myths, legends and monsters as reality, so it was not unusual to believe in both science and the existence of dragons and unicorns.

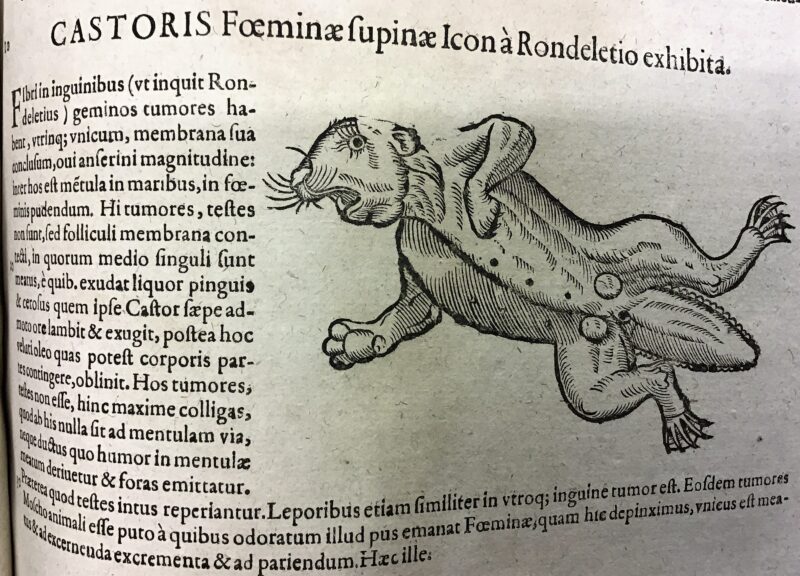

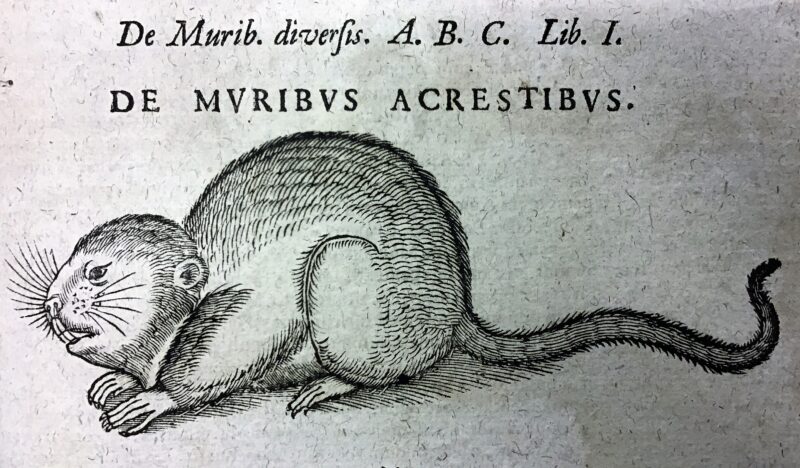

Many published naturalists at this time didn’t travel far. Instead they relied on (sometimes distorted) descriptions of animals that fellow travellers and explorers had seen in order to create an image. As a result, depictions of animals weren’t always entirely accurate, and mythical creatures such as satyrs, hydras and sea monsters were often to be found depicted in the pages between horses and geese. They couldn’t prove that the creatures described didn’t exist, and there was no David Attenborough on hand to tell anyone otherwise, so everything was included. For example, many sailors told of amazing sea creatures and mermaids on their journeys, but it must be remembered that fresh water wasn’t available and rum was the drink of choice onboard! They may well have just been exaggerations of quite normal, or now extinct, sea creatures.

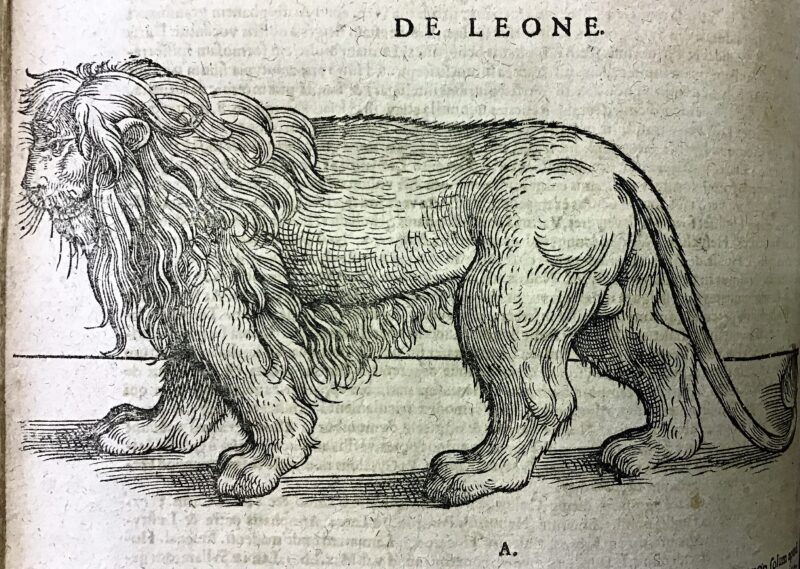

One of the earliest published naturalists was Conrad Gesner. A Swiss national who rarely travelled far and who died from the plague at the age of 49, he published widely on a number of subjects. His magnum opus however was the five volume Historia Animalium (1551-1558), comprising more than 4,500 pages of images and descriptions of all known creatures at that time. He combined information from his research of historic sources, such as the Old Testament, Aristotle and Pliny, as well as folklore and medieval bestiaries, with his own observations to create the first comprehensive description of the animal kingdom. Historia Animalium was also one of the first books to be illustrated with woodcuts drawn from personal observations by Gesner and descriptions from his colleagues. It was published in the two recognised scientific languages of the day – Latin and Greek.

The book wasn’t without its controversy. Pope Paul IV added Historia Animalium to the Catholic Church’s list of prohibited books. Gesner was a Protestant and the Pope felt that his faith contaminated his observations and writings.

The legacy of Gesner and other naturalists of his time cannot be underestimated. They were the people who established the basis of the science of zoology, classification and taxonomy – the first to try to categorise like groups of species together. Their drawing style and technique still influence the way scientific illustration is presented today. And the volumes provide an important snapshot into society’s knowledge, and beliefs of that time, where mythology and science were beginning to disconnect.

Morrab Library is fortunate to hold the first two of the five volumes of Historia Animalium in its collections. Our editions are dated 1617-1620, around 70 years after they were first published, and they are a very special treasure amongst our collections.

Lisa Di Tommaso, Librarian