We really enjoy chatting with you when you return your recently read books to the library and wanted to share some of your recommendations with fellow members. We will be sharing your reading suggestions at the end of the each Fortnightly Links email and adding them to this rolling blog.

Your reading tastes are wonderfully eclectic and inspiring so this section will be a chance to tell your fellow members about books you have borrowed (and enjoyed!) from the Morrab Library.

If you’d like join in, please send us a few sentences (up to 100 words) on a recent book you’ve enjoyed to enquiries@morrablibrary.org.uk and we’ll share your tips.

Susanna, Mother of the Wesleys, by Rebecca Lamar Harmon, recommended by one of our volunteers

“Susanna, Mother of the Wesleys, published 1968, by Rebecca Lamar Harmon (wife of a Methodist bishop in the USA and former editor of The Methodist Church, and who died in 1980).

Susanna Annesley (1669-1742) the daughter of an eminent Puritan was a fascinating woman, courageous and indomitable. She married Samuel Wesley, not a nonconformist but an Anglican priest, who was scholarly and, at times, impractical. Together they had nineteen children, only nine of whom survived to adulthood. Best known were the boys, Samuel, Jr., Charles, and John, the founder of Methodism, and much has been written about them. However, little was known about the women, Susanna and her daughters, Emilia, Susanna, Mary, Mehetabel (Hetty), Martha, and Kezziah. Rebecca tells the intriguing story of the whole family and Susanna Wesley’s influence. From the day she and her husband moved into the Epworth parsonage, in remote swampy Lincolnshire, until her death, Susanna is portrayed as a woman of uncommon spiritual, intellectual, and physical strength, albeit within what must have been for her the confining social constraints of rural 18th century England.

Rebecca discusses Susanna’s novel approach to home schooling, and how she and Samuel provided for the family on a country rector’s paltry income. And of the differences between them concerning the raising of their daughters, especially about Hetty, who conceived ‘out of wedlock’ and was disowned by her father.

This book, published in the USA in 1968, is a book that deserves to be read as much for social history and 18th century family customs as for its contribution to Methodist history.”

Un Avion Sans Elle by Michel Bussi, recommended by one of our volunteers

“An airliner with two three-month-old babies and their parents on board crashes into a forest on a Swiss mountainside and bursts into flames. The only survivor is one of the babies, miraculously unharmed, but with no identifying features to prove her parentage. Both sets of grandparents bitterly contest their right to her adoption, which is finally settled by a judge in favour of the least well-off family. The frustrated wealthy grandparents thereupon hire a private detective to investigate the girl throughout her life until she is eighteen, when she can then decide for herself to which family she would belong, guided by the detective’s report.

In this long, French, detective roman, high tension – and a romance – is maintained to the very last pages as the story twists and turns between families, siblings and readings of the detective’s report as he repeatedly returns to the site of the crash.

A cracking read for a long wet weekend.”

“The SAD Detective by Colin Stringer, recommended by Linda Camidge

“SAD in this instance does not mean ‘sad’ or even ‘emphatically sad’. Nor does it mean that the main character suffers from Seasonal Affective Disorder. No: D I Rob (who is not a Detective Inspector, either) suffers from ‘social anxiety’. Although in fact his choices and behaviours struck me as a witty representation of the entirely normal. Slightly exaggerated for comic effect, perhaps – but D I Rob thinks and does the kind of things that we all might have thought or done once, or might in the future, or that are even part of our habitual behaviour.

The self-deprecating D I Rob is hardly a hero, but he’s much more than a comic cipher. As the plot unfolds, our enjoyment of his self-deprecation and self-inflicted plights is gradually overtaken by respect for a character who in more than one sense finds his purpose, his place in the world. And the plot itself is masterful, with a few surprises and everything tied up in satisfying fashion at the end.

Without being an ‘easy-read’, this is nonetheless an easy book to read. The chapters are short, and their intriguing names made me want to allow myself the luxury of reading the next and finding out where in the text the chapter title might be waiting. I am not an adept reader of mysteries and am also useless at puzzles, so I appreciated the careful way in which Colin Stringer subtly re-caps and reminds the reader of key details where necessary. He has also created a manageable number of characters, and differentiates clearly between them in terms of appearance, catch phrases and personality.

I enjoyed the local colour – the representation of the Morrab Library is both endearing and accurate – and I liked the way that the characters are presented with affection. All – or almost all – are forgiven. There is no brutal showdown: instead, we reach the end with a sense of satisfaction. The mysteries are solved and everyone is ready to move on. Not so much Macbeth, more The Tempest

But there the similarity ends. For this is not a final published work, but a first. And I, for one, hope that Colin Stringer will go on to write more.

Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton, recommended by one of our volunteers

“In a remote corner of New Zealand a group of radical environmentalists surreptitiously cultivate crops in patches of waste ground. Their principles are compromised when they accept financial support and go big time on a large abandonned estate owned by a multimillionaire who made his money making drones. The consequences for them all are devastating. Birnam Wood – the name of part of the estate – is a compelling read with a cliffhanger ending – and a moral message. Recommended.”

Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell by Susanna Clarke, recommended by Matt Black

“Magic has been absent from Britain’s shores for hundreds of years, until now. In this completely wonderful novel set during the Napoleonic Wars, two rival magicians struggle to bring back magic to its once respectable heights and deal with the unknown dangers of fairy folk…

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall -by Anne Brontë, recommended by Ruth Baigent

“Anne Brontë’s The Tenant of Wildfell Hall is an exceptional work of genius. She has created a focal female protagonist who is powerful, irascible, hard edged, and magnificent, yet she is like the classically male characters (Mr Darcy, Heathcliff, etc) whose hard edges mark their romance, indicative of their lonely survival in a life of freedom, love and fierce nobility of spirit: an articulation of an integrity, vastly misunderstood by the world that doesn’t know her. I loved to find this spirit in a female character, and find her loved by a good and devoted male protagonist, weaker than her, but also unequivocal in his love, when he finds it. She draws him out. She calls him deeper, he follows. For me, this book felt radical and awesome. Please also read Agnes Grey.”

The Harry Potter books -by J.K. Rowling, recommended by 12 year old Hazel

“The Harry Potter books are such fun due to the gripping plot and, of course, the fantastic characters.The books follow Harry Potter, famous due to his impossible survival of the killing curse as a baby, who is thrown into the wizarding world abruptly after his twelfth birthday. He soon becomes friends with Ron and Hermione, creating an iconic trio to continue throughout the series. As the story progresses, the world that they face becomes more dangerous, their challenges more demanding and their lives more difficult. These books are suitable for ages 8+ and I highly recommend giving them a go.”

Sapiens – A Graphic History by Yuval Noah Harari illustrated by David Vandermeulen and Daniel Casanave recommended by C J Van Dop

Back in the day, comic books and comic book art had a rather juvenile and vulgar reputation. Aside from cartoon capers by various animals, sometimes more serious attempts at visual subject matters would arise – Robin Hood, Westerns etc and depend on engaging graphic style for their appeal. Since the 1960s, new avenues in comics appeared in the shops of Head Comix – mainly counter-cultural, psychedelic or nihilistic by nature then publications pointed toward a medium outside T.V or mainstream literary publication for artists and writers to get public exposure and sales. Recently subjects from Margaret Atwood’s writings to the proliferation of MANGA have become widely accepted.

Among these many offerings this year comes ‘SAPIENS’ a broad and exciting visual journey charting the emergence of mankind no less. In the format of a youngster with big questions about where we have all come from and how it is that we are here, we meet some lucid, informative and cool ‘professors’. The illustrations use a pared down but broad graphic layout to depict different scenes of the journey. Many aspects of early ape creature lives are spotlighted. How for example it is that six separate branches of early man lived in different parts of the globe – from homo floresiensis way out east to our very own Neanderthals – but only we as homo sapiens sapiens survived but flourished to become Lords of the Universe? There are of course many unanswered questions and some parts of this long march of ours is probably unknowable. What did happen to an old relation to the Neanderthal? We all share 2-6% of his DNA but did we assimilate him in prehistory or did we simply kill him? Sapiens, it seems, are not terribly good at coexisting with other animals or humans. These changes from man to the hunter-gatherer through manch pastoral gardens to man the builder of cities and Sapiens is, eor, graphically prorated as set out. A companion volume called ‘Civilization’ has been published when it was doubted many of these features about our evolution will be under the spotlight.

I tried to dislike SAPIENS. How can 5 million years of human evolution be addressed in a cartoon strip?! But I quickly became a fan. I want to recommend this – it’s not hugely expansive but a weighty hard back tome – to anyone or anyone’s children who are interested in learning more about our remarkable journey but don’t know where to begin.

The English Patient by Michael Ondaatje – recommended by David Yard

“An exquisitely constructed story of characters pushed apart and pulled together during the Second World War. Whilst the film presents the story as a powerful romance, the novel asks broader questions about the power of nationality, ownership, and belonging. Is the English Patient actually English and does it really matter?”

A Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan – recommended by Becky Wildman

“Around fifty pages into Jennifer Egan’s A Visit From the Goon Squad, I realised I was going to love this novel. Thirteen interrelated stories centre around Bennie Salazar, a record company executive, with events taking place from the 1970’s to an imagined present day. Egan moves effortlessly though the lives of the characters, showing how the fortunes and events of each are connected and intertwined. Shifting the perspective of both the narrative and the order of chronological events, she creates a nostalgic, charming and imaginative tale of lives forming and passing around the entertainment industry. She uses a range of creative techniques to present the different viewpoints expressed within the novel, which make it both effective and progressive and a truly enjoyable read.”

The Museum Makers: A Journey Backwards by Rachel Morris – recommended by John B.

“As a professional adviser to museums Rachel Morris illustrates their cultural importance, whether local or national(contemporary Vandals in County Hall please note). But what gives this marvellous book its particular appeal is the author’s attempt to construct what she calls “A Museum of Me”. The contents of her museum comprise long neglected family records, letters and photographs she has inherited together with what she learned from her Gran’s memories. When her mother died young, Rachel and her two siblings were effectively abandoned by their father Guido Morris who as a printer and publisher drank his way round post-war St Ives for the best part of a decade. The formidable Gran, Margaret Birkinshaw, kept the impoverished family together. In reconstructing her family history Rachel ranges from the late 19th to the early 21st century and, despite some dark episodes, her memoir is a wonderfully positive act of recovery. Any fan of “Whose life is it Anyway?” on TV will love this.”

Scythe by Neal Shusterman – recommended by Josie Yard

“I don’t normally enjoy dystopian books, but Scythe put such an unexpected spin on this genera you couldn’t pick out another book like it. It’s set in a future where humans have overcome death, and so they have a group of people with the ability to kill, called Scythes. The story follows two apprentice scythes (Citra and Rowen) who are taught the art of killing and start to find that the perfect world they knew has been crumbling before their very eyes. Some scenes may be too gruesome for ages 11 or under but I recommend it for teens.”

Cedric Morris – A Life in Art and Plants by Janet Waymark – recommended by Helen Moulsley

“This book is a visual delight and takes us on a journey of the life of the artist and plantsman Cedric Morris, a life he shared with his lifelong partner artist Arthur Lett-Haines who managed their business affairs.

After sojourns in Cornwall (Zennor and Newlyn), Paris and London, and Pound Farm in Suffolk, they opened the East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing at Dedham in 1937 (relocating to Benton End after a fire) primarily as a means of earning a living. Students over the years included Lucian Freud and Maggie Hambling. The style of teaching was to guide and advise if needed; meals and accommodation provided by Lett were bohemian.

Benton End enabled Cedric Morris to indulge his interest in plants, especially irises, producing over 90 named varieties, which of course he painted and which are shown in the book. As a plantsman he became friendly with and influenced gardener Beth Chatto among others.

As well as being a biography of Cedric Morris the chapters in the book act as mini-biographies of those whose lives were touched by Cedric Morris. The short chapters are illustrated by his work, and that of his students as well as by many photographs. The oil on canvas by Hambling entitled Lett Dreaming 1975/76 (Lett died 1978); and her charcoal of Cedric in Ipswich Hospital the day before he died (1982), bring this wonderful book to its close. The inscription on Cedric Morris’ gravestone in Hadleigh cemetery describes him as “artist plantsman 1889 – 1982”. Lett’s gravestone is set back slightly behind Cedric’s. “

Wonder by R J Palacio – recommended by Ilani

The High House by Jessie Greengrass – recommended by Jane Prince

“I had just finished reading this book before the U.K. was experiencing its own extreme weather event, emphasising the theme of the novel. The plot revolved around a group of young people who survive devastating floods and unnaturally long hot summers because of the presence of Francesca, a climate activist who realises that time is running out quicker than anyone believes and takes steps to ensure the survival of her son Pauly and his older step-sister, sacrificing her own family life to do so. The book is both touching and chilling and is eminently readable. “

The Uncommon Reader by Alan Bennett – recommended by Jenny Dearlove

“A cleverly plotted, warm and hilarious fantasy about Her Majesty getting a passion for reading. It makes the world seem brighter and full of possibilities”.

South from Granada by Gerald Brenan – recommended by Harry Carson

“Perhaps the so-called Great War, or its effects, continued far beyond 1918. For those young men not slaughtered, disabled or disfigured and with a yearning need to make sense of the world, travel offered a chance to breath air. The destruction, chlorine and trenches were exchanged, for those with income, for mountains, sunshine and a chance to live in an almost pre-industrial world.

Gerald Brennan did this and left for us a compassionate record of Spanish villages unspoiled by rapid progress; villages peopled by young lovers, old widows, suspect officials and a realisation that nature, even in hot and hostile places can and does provide if we are willing to be patient.

His experiences with and without the villagers showed him not only how a poor arid village in the 30s lived but also, to an extent, how England once, before, shortly before, had also enjoyed , if not Jerusalem, certainly a peaceful and pleasant land.

A wonderful read. Even better the second time.”

This Changes Everything – Capitalism vs. The Climate by Naomi Klein – recommended by John Trigg

“An in depth exploration of the climate / environment from a left wing viewpoint. Exposes the un-caring world of business and trade, how the earth becomes just a resource to be exploited. Forever dominated. And governments need to be much more involved in controlling this.”

Kingdoms of Elfin by Sylvia Townsend Warner – recommended by George Care

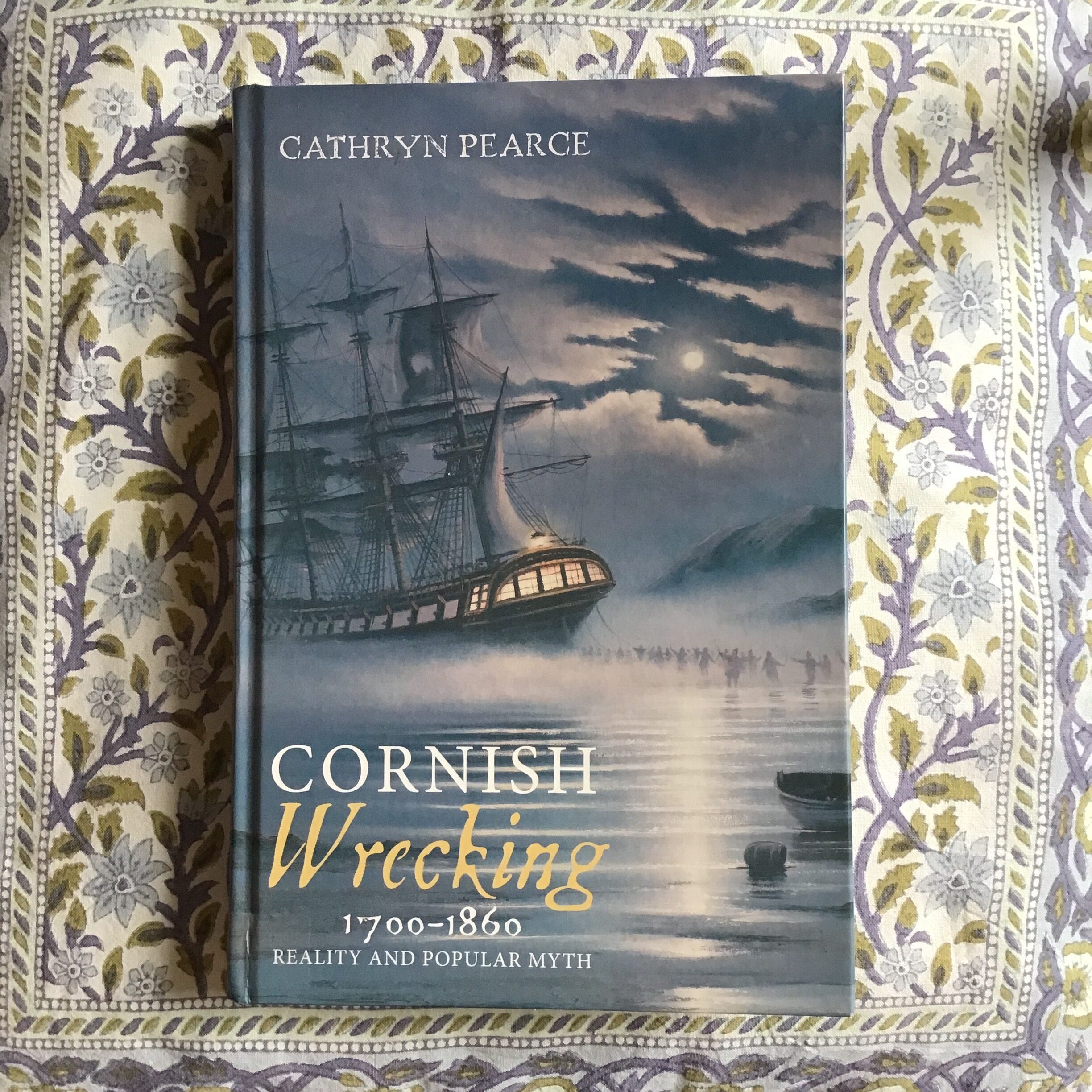

Cornish Wrecking 1700-1860: Reality and Popular Myth by Cathryn Pearce – Recommended by Ruth Towse

I found this splendid book lurking in the Cornish collection. Published in 2010, it shows little evidence of having been taken out of the library. It deserves a much wider readership, and my guess is that it will soon get it. There is likely to be a surge of interest in the topic as Ethel Smyth’s opera The Wreckers is to be performed as part of Glyndebourne Opera’s summer season and at the Proms, no doubt awakening interest in the more lurid view of wrecking, which Smyth, along with many others, adopted.[i]

Pearce’s book is extremely well researched and is engagingly written. It seeks to disprove the trope of wrecking as the murderous luring of boats to doom by misleading use of lights, pointing out that on the one hand, so-called wrecking consisted of several acts – harvesting (beachcombing), plunder, collection of flotsam, jetsam and lagan (items cast off to save the ship) – most of which were legal over the period she covers, and on the other hand, that the portrayal of evil wreckers was part of fears in the period about the potential ‘wrecking’ of society by the lower classes. In fact, wrecking was not confined to Cornwall and most cases took place elsewhere, notably along the counties of the South coast. She identifies the changes in attitude to these different acts by society and the state (Methodism, the Customs and Excise Office) and traces the history of the laws and practices relating to them.

Retrieval of goods from wrecks formed part of manorial rights and in Cornwall ‘royalties’ from them were due to the lords of the manor – the Arundels, Bassetts, Godolphins, St Aubyns, Duchy of Cornwall – and sometimes to the Church. Wreck agents were appointed by them to deal with the collection and sale of the goods from wrecks and the reward of the ‘country folk’ and tinners who gathered them, as well as the disposal of the bodies of those who had drowned. This system continued for centuries, only involving the state in the form of Customs officers when wines, tobacco and tea etc. were involved. When lands were sold, the rights to the royalties from wrecks on them were not part of the deal, leading to considerable complexity about their ownership and disputes that were sometimes settled in courts. The story of how the system evolved over the years is fascinating and Pearce tells it clearly, rigorously citing sources from lawsuits to newspaper reports. Over time, though, these rights came to be challenged by the state; laws and social attitudes changed and, moreover, there were fewer wrecks as ships were better built and navigation devices (such as light houses) improved.

Overall, the book offers insight into both Cornish customs and history, revealing how misunderstanding of wrecking and the vilification of the rural poor came to dominate the topic. It is as much a social history as well as one of maritime law, the subject in which Cathryn Pearce is specialised. Mainly, though, it is a jolly good yarn about aspects of life in Cornwall that many of us know little of.

Ruth Towse

01/05/22

[i] The synopsis may be viewed on https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Wreckers_(opera)#Synopsis for Smyth’s biography see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethel_Smyth