Delivering The Goods – a short story by Julia Grigg

Morrab Library is open again, although in a very limited capacity. The necessity to keep staff, volunteers and members as safe as possible is our first priority, and we will need to continue to work within the context of health and safety legislation and best practice guidelines for libraries to achieve this.

Please note we will close for the Christmas period from 4.00pm Saturday 19th December until 10.00am on Wednesday 6th January.

It needs to be said that while the staff will do all it can to make the library as safe as possible, we cannot of course guarantee it 100%, so each member will need to make their own decision about whether they feel they can visit.

Opening hours and access

While you are with us

Loans and Returns

Amenities

Cleaning

Please contact the Library (enquiries@morrablibrary.org.uk), or leave a message on 01736 364474 and we’ll call you back, if you have any questions or concerns.

We would also like to offer my assistance to any of you who will need to continue to self-isolate and won’t be able to visit, or do not have anyone who can borrow books on your behalf. Please get in touch so we can find a way to help you if we can.

I know this remains a less than ideal situation, but hopefully it won’t be too much longer before we can return to the normality of the Morrab Library we all love so much. Thank you so much for your wonderful support throughout lockdown, and as we move forward into the new year.

Lisa Di Tommaso

Librarian

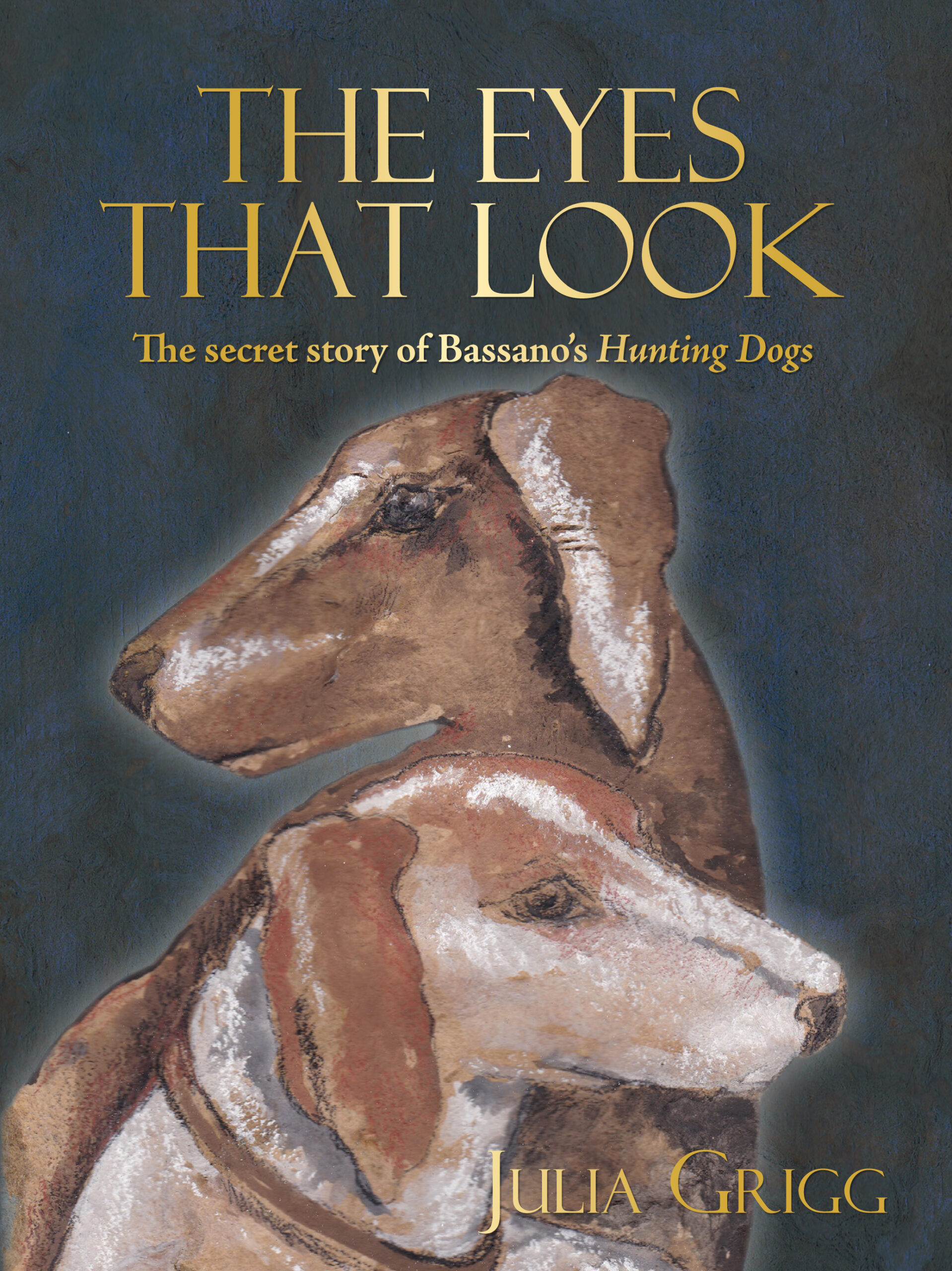

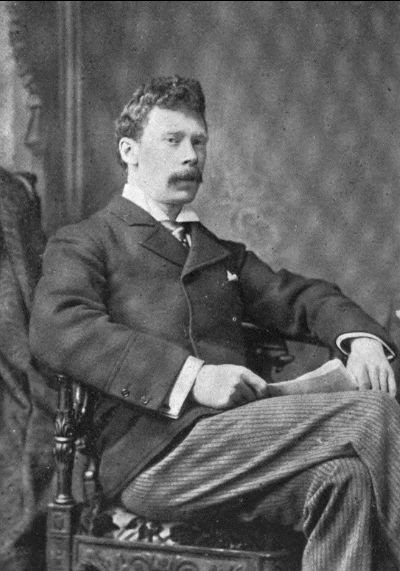

Library member Dr Robin Agnew has written an essay about the Victorian publisher George Smith (pictured above), his career and his friendship with Charlotte Brontë. You can read it as a PDF here.

We’ve recently added a new book to the library collections. A Cornish Cargo: The Untold History of a Victorian Seafaring Family, by Alison Baxter. It tells the true story of Alison’s ancestors, from their move to Hayle to their subsequent adventures throughout the 19th century. Her blog follows below.

A Cornish Cargo

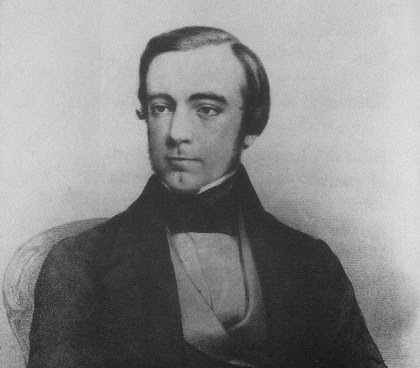

In 1839 a little girl stitched a neat sampler, the hundreds of tiny crosses displaying her command of the alphabet, the verse a reminder of her Christian faith. The child, Joanna Woolcock Dupen, was born in 1832 in Penzance, and baptised in the Wesleyan chapel there. According to the certificate, her father was working as a confectioner, which seems a remarkably tame occupation for a man who had previously sailed out of Falmouth to Ireland and the Mediterranean, braving the heavy seas in a small, single-masted cutter. He must soon have tired of stirring vats of sugar to satisfy the sweet tooth of the townsfolk, because when Joanna was three years old, the family moved to Hayle. Her father, Sharrock Dupen, had taken the job of steward on the new steam packet Herald, a vessel that was to transform the journey from Cornwall to Bristol.

The child Joanna was my great-grandmother’s oldest sister, the first of a long family of thirteen, and Sharrock Dupen was my great-great-grandfather. An ordinary man, like most of our ancestors, but emblematic of an age when the power of steam was changing the world. Every week, the wooden Herald set off from the quay at Hayle, over the sandy bar and out into the bay for the overnight journey along the north coast, past the treacherous rocks of Hartland Point and into the mouth of the Avon. She carried tin, copper and iron goods from the foundries, returning with a cargo of everyday necessities for the shopkeepers of Hayle: coffee, butter, soap, needles, candles and buttons. Sharrock Dupen, a rotund, cheerful man, as we can see from his portrait, supplied the passengers with food, drink and reassurance. ‘We shall have a voyage as calm as a sail in a duck pond,’ he told one anxious traveller mendaciously.

When I inherited Joanna’s sampler, it inspired me to trace the history of the Dupens. I knew little about them apart from the fact that they were said to be of Huguenot origin. The one story I had been told was, I thought, bound to be apocryphal. We all inherit family myths that we enjoy without fully believing in them. Mine is about vegetables. In the 1930s my grandfather, a sceptical engineer, wrote this letter to the editor of the Morning Post: Mr Dupen’s Grandchild on a Family “Fairy Story”

Sir – With regard to your announcement about the Cornish Broccoli industry in Saturday’s issue of the “Morning Post”, as children we were often told that our grandfather – the Mr Dupen mentioned – first grew Broccoli in England, but I’m afraid we rather regarded this as some subtle kind of fairy story to encourage our appetite for the vegetable! From the announcement it would appear that he really was interested in the broccoli plant, but are there any records to show that he did actually introduce the plant into England, and if so, from where?

He thought it was a fantasy and so did my father, who passed it on to me and my brother as way of encouraging us to eat our greens. But now that the newspaper archive is searchable online, I was able to uncover the true story of how my great-great-grandfather is credited with rescuing the economy of Cornwall.

He was not in fact the first to grow broccoli but the first to transport it from Hayle to Bristol in the 1830s. An initial shipment of four dozen heads became fourteen dozen the following week and Sharrock Dupen had a virtual monopoly of the local trade until the growers themselves cut him out. Twenty years later, the steamer from Hayle was transporting 860 baskets containing fifteen to eighteen dozen heads of broccoli each. In a commemorative speech in 1933, the Lord Mayor of Bristol attributed the prosperity of Cornwall to this vegetable trade. The miner, so it was said, had become the broccoli grower.

My book, A Cornish Cargo, started with Sharrock Dupen but turned into an account of how his children also had their lives changed by the coming of steamships and railways. The boys went to sea at a time when it had become possible to serve as an engineer instead of an ordinary sailor and I was able to trace their voyages around the world. The girls too left home, travelling by steam packet to Bristol and onwards by the Great Western Railway to take up posts as governesses and schoolteachers. The only Dupens left in Cornwall now lie in the churchyard in Hayle. People sometimes tell me I’m lucky to have such interesting ancestors to write about, but I believe everyone has family stories that are worth telling. History is not just about famous people, battles, and politics. It’s about how ordinary people lived their everyday lives.

In normal times, Morrab Library would be hosting a large event (with lots of cake!) to celebrate the launch of this major new website exploring the life and works of Arthur Quiller-Couch. But instead, we’re delighted to tell our members all about it through this blog.

The site is curated by library member and leading researcher Andrew Symons, who has developed the articles and resources it contains in collaboration with Morrab Library, which holds collections of the works of Q and other members of the Couch family.

The product of many years’ study, the website offers the largest and most authoritative online collection of research into Arthur Quiller-Couch. It includes studies of many of Q’s literary works and the cultural landscape in which he worked. You will also find short articles, maps, summaries, chronologies, biographies of Q and his family – and a wealth of other resources – all of which help to illuminate his writings.

Many people in Cornwall will be familiar with the name of Q but may not know the extent of his work. He was a popular novelist with an international reputation, a poet, a literary critic, an anthologist and an academic who championed the importance of literature in the education of young people. Born in 1863, he lived through an extraordinary period of British history until his death in 1944. The lives of his grandfather, father and uncles also reveal much about the fascinating scientific and cultural history of Cornwall in the nineteenth century.

This site is designed to act as the fulcrum for wide-ranging study and exploration of Arthur Quiller-Couch and his writings. It welcomes submissions of original academic work from other researchers.

It is hoped that the website will also provide an introduction to the works of this outstanding figure in Cornish cultural life. Newcomers to Q may be surprised to find how contemporary his voice sounds today. Once known as the ‘Greatest Living Cornishman’, Q was a brilliant man who deserves to be rediscovered. The hope is that this important new website will help in that process.

Library member Kensa Broadhurst is studying at Exeter University, and has been using Morrab Library’s extensive archive collections for her research since we re-opened. She came across two fascinating documents, written by prisoners of war. The library holds facsimiles of their diaries. Here’s Kensa’s take on them….

I have been working my way gradually through the archives at the Morrab Library whilst researching for my PhD. The letters, journals and notebooks held in the Morrab archives are a real window into the past and offer a fascinating view of not only daily life, but contemporary views on the wider world too.

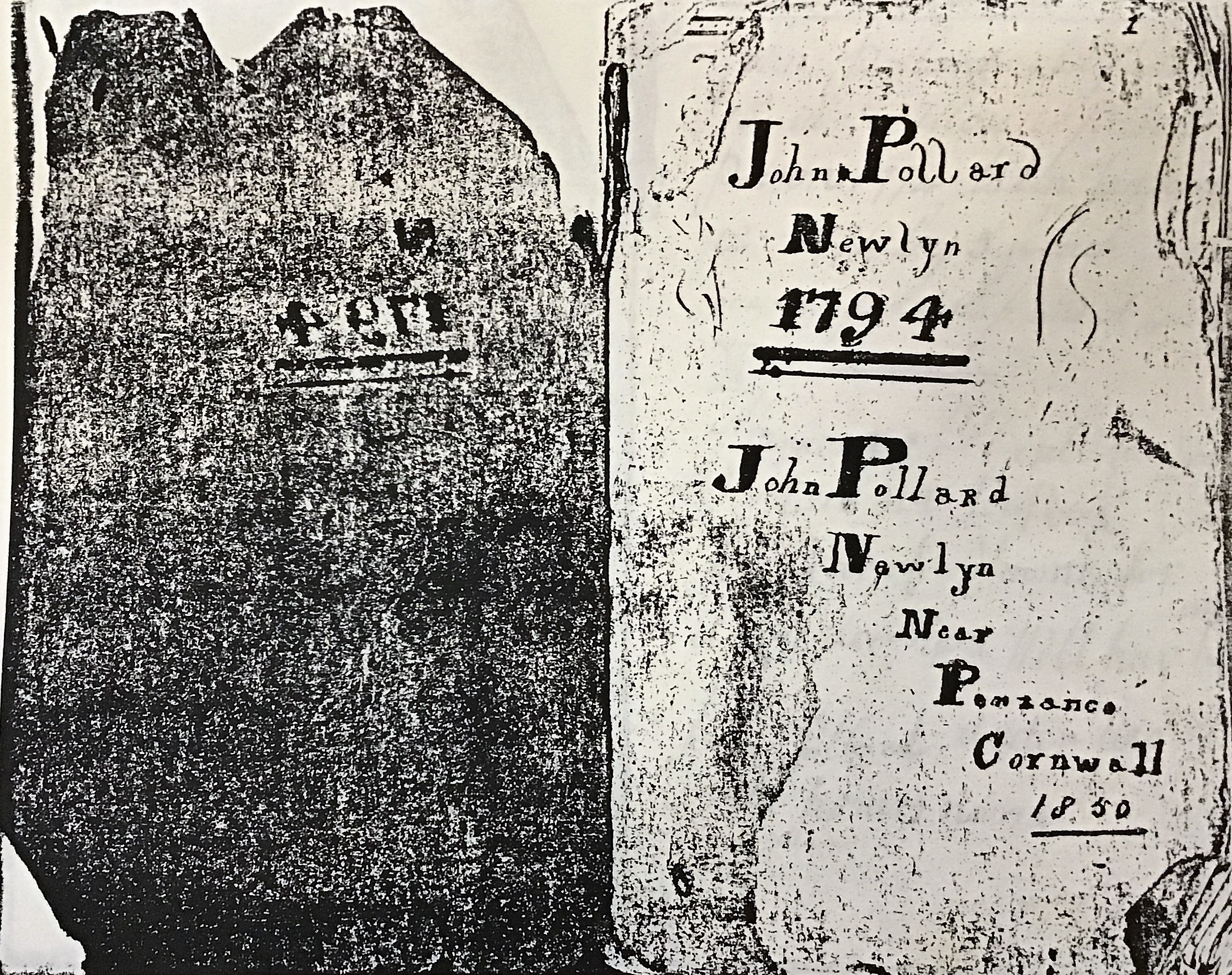

Two of the most interesting documents I have read recently concern Revolutionary France and the Napoleonic Wars. John Pollard, a ship’s Captain from Newlyn, was a prisoner of war in France from 1794-95 who kept a journal for a large portion of his time in captivity. Similarly, Captain James Quick was held captive from 1810-14. He wrote a series of letters to his wife in St Mawes detailing his life as a prisoner.

Pollard tells us that he began to write his journal only after several months of captivity and so it is unclear whether his account of this early time is copied from elsewhere or based on memory. Pollard’s account not only details the trials, tribulations and practicalities of life as a prisoner of war, but offers a contemporary view of wider events in Revolutionary France. Some of these are hearsay, or titbits of news picked up sometimes long after the events in questions, such as the death of Louis XVII, or the results of Naval Battles, but through Pollard’s journal we are also able to track the effects of inflation and food shortages on France at this time. The price of bread steadily increases from 1 to 15 livres per pound for example. I found it fascinating to discover that whilst the prisoners were given a certain food allowance each day, Pollard was also able to work and earn money. Although there were times when he was unable to work due to illness, the weather or changes in regulations within the prisons in which he was held, at various times Pollard works as a gardener, builds roads, repairs fishing nets, heaves rubbish and works in a grocers, variously grinding pepper and coffee. We also hear of other prisoners getting drunk in the local public house, starting a fight and breaking things! Pollard also keeps track of the escapes, and attempts, of other prisoners. Some of these are more successful than others.

As Quick’s letters were written with an intended recipient in mind, his wife, they chart a wider range of emotions than Pollard’s journal. We sense his frustration in the early letters when Quick has evidently not received any letters himself, then relief that he does finally hear from his wife, coupled with annoyance that his brothers do not think to write to him. The letters also discuss the practicalities of receiving post (via the Transport Board seem to be the most reliable means), and the frustrations of not being a regarded a Prisoner of War by the Committee for Prisoners of War at Lloyds of London (and therefore able to claim money for support) as he had been shipwrecked on the French coast and then imprisoned. The French view was that all were regarded as prisoners of war, whether shipwrecked, captured or forced to seek shelter in a French port by adverse weather. Lloyds evidently wanted to avoid paying out any money! Quick’s letters also give us an insight into contemporary networks within Cornwall. In his letters he lists other Cornishmen with whom he is held captive and their hometowns in order that his wife and get word to their families of their situation. As well as men from Mevagissey we hear of several men from St Ives. We learn Quick spent his time in captivity learning French and some of the language begins to find its way into his writing.

Examining documents from the past not only makes me realise how privileged we are to have a wealth of archives, such as those held at the Morrab, but also make me feel more connected to the past. As I drive around Penzance and the local area, places which feature in the documents I have read now jump out at me as I think about the people who lived there and the events which took place which I have discovered.