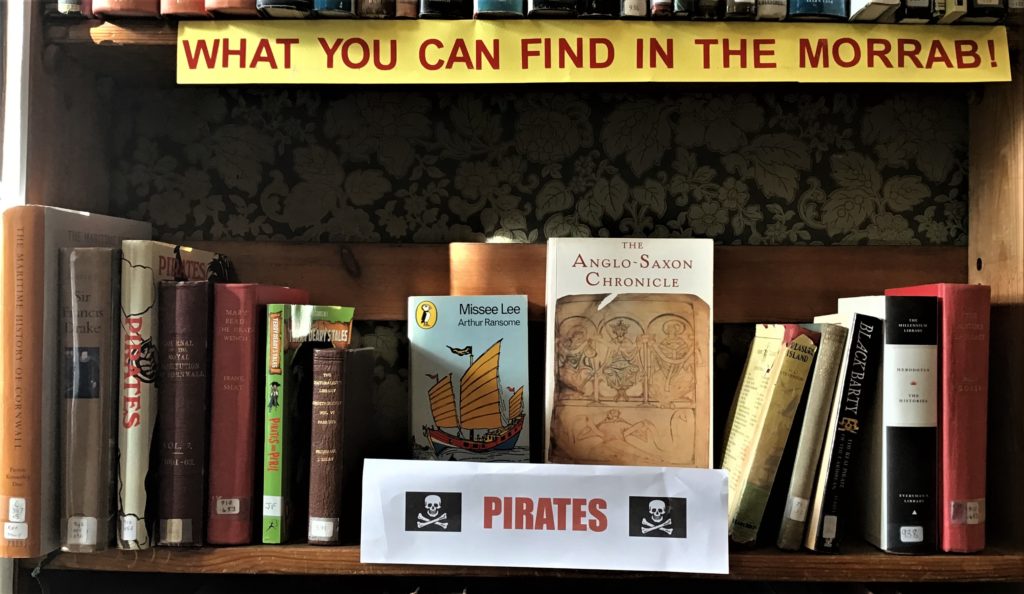

A short history of photography: a snapshot

The Photographic Archive is one of the treasures of Morrab Library. Run by a team of volunteers, it is open to the general public, at no charge, every Thursday morning. Several donated collections form the archive of 15,000 glass and celluloid negatives, and black and white prints. They capture images of life in West Cornwall, and beyond from the early days of photography in the mid-19th century until the late 1970’s. Subjects range from studio portraits to sport, fishing to flower-picking and shops to shipwrecks. A digitisation project is currently underway – more information can be found here: https://morrablibrary.org.uk/photo-archive/

The Photographic Archive is one of the treasures of Morrab Library. Run by a team of volunteers, it is open to the general public, at no charge, every Thursday morning. Several donated collections form the archive of 15,000 glass and celluloid negatives, and black and white prints. They capture images of life in West Cornwall, and beyond from the early days of photography in the mid-19th century until the late 1970’s. Subjects range from studio portraits to sport, fishing to flower-picking and shops to shipwrecks. A digitisation project is currently underway – more information can be found here: https://morrablibrary.org.uk/photo-archive/

Lesley Billingham, one of our Photo Archives volunteers has written a short history of photography, to provide some background and context to the amazing images we hold in our collections……

From the earliest days of humankind people must have seen, by accident, when the sun was at the ‘right’ angle, the dwelling in darkness, a chink in the door; suddenly the scene outside projected, in colour, upside-down on the inside wall. A vision, an image, a mystery.

We have to fast-forward millennia, because very little information exists until this phenomenon became a drawing aid to painters in the 15th century. Leonardo Da Vinci described the principle, “Light entering a minute hole in the wall of a darkened room forms on the opposite wall an inverted image of whatever is outside”. A camera obscura, literally a ‘dark room’. Polished convex mirrors were used and then lenses to sharpen the image. The paintings from this era onward show a significant change in perspective, flat two dimensional images replaced by a more naturalistic three dimensional perspective, just like a photograph.

Experiments in the early 18th century by German physicist Johann Heinrich Schultz established the light sensitivity of silver halide salts, the first glimmer of things to come. In the early 19th century, powered by the industrial and scientific revolutions, came a flurry of excitement around making a photograph that would not fade. In England Thomas Wedgewood, son of the potter Josiah Wedgewood, reported his experiments in recording images on paper or leather sensitised with silver nitrate; he could record but not make them permanent.

In 1802 the famous scientist and poet Humphry Davy, published a paper in The Journal of the Royal Institute on the experiments of his friend Wedgewood, “An Account of a Method of Copying Paintings upon Glass, and of Making Profiles, by the Agency of Light upon Nitrate of Silver, with observations by Humphry Davy. Invented by T. Wedgwood, Esq.” This is the first known account of an attempt to produce a photograph. How exciting to think that the invention of photography was described by a man born and raised in Penzance, who may have even visited the nascent Morrab Library.

Ultimately William Henry Fox Talbot, an English mathematician and scientist using ‘fine writing paper’, sensitised with silver nitrate and fixed with a sodium chloride solution, produced a photograph, but this was only stable for a short while due to inadequate fixing. When his friend, the astronomer Sir John Herschel, suggested fixing the negatives with sodium hyposulphite the images did not fade. We still use ‘hypo’ or ‘fixer’ in modern darkrooms. Meanwhile, in 1826 Nicephore Niepce, an amateur inventor, made the first known photograph, with an exposure of eight hours, of the view from his window at Gratz. Louis Jaques Mande Daguerre, a French scene painter, formed a partnership with Niepce in 1829, but Niepce died four years later, and building on his partner’s work Daguerre managed to make and ‘fix’ images using a much shorter exposure time. This became the daguerreotype process created on a polished metal plate sensitised with silver and developed with mercury vapour, a very toxic process.

Fox Talbot, aware of Daguerre’s work in France, hurried to complete his process and both the daguerreotype and Talbot’s salted paper prints, later renamed the calotype, were formally announced in 1839. The daguerreotype was known as, ‘the mirror with a memory’, and created the most beautiful, extraordinarily detailed images, but being made on a metal plate, each was unique and not reproducible. The calotype, however was made from a paper negative which could be printed many times, although without the sharp detail of the daguerreotype. In 1851 Frederick Scott Archer, a sculptor, invented a method of sensitising glass plates with silver salts by the use of collodian. Within a decade collodian plates completely replaced both the daguerreotype and calotype processes, reigning supreme in the photographic world until the 1880s.

In 1857 cartes de visite were introduced to England. A camera with multiple lenses created a sheet of portraits which could be cut up and presented to your friends. However it was not until J.E. Mayall took carte photographs of Queen Victoria and her family in 1860 that the carte de visit collecting craze exploded. Celebrity cartes were sold in stationer’s shops, just like picture postcards today. These would be collected and mounted in albums, remaining a popular format until the beginning of the 20th century.

This is where our collection begins. The oldest images held here in the Morrab Library Photographic Archive are in an album from the 1860s, containing many cartes de visite of the great and the good of Penzance. These photographs have been carefully collected with hand written titles, many family names are still present in this area today. There are one or two photographs of elderly people in the album and we find ourselves gazing into the eyes of someone born in the 18th century.

Many processes were invented in the following years, the woodburytype, tintype, ambrotype, cyanotype and many more. The new technology of photography required the mass production of materials. Albumen, from millions of hen’s eggs, was used in the manufacture of printing paper. Silver halide salts were mixed with the albumen, spread on paper and dried to form the light sensitive layer. Later, gelatine became more commonly used for this purpose. In the 1880’s an American, George Eastman developed a camera complete with a roll of film, made of celluloid, a kind of early flexible plastic. It is believed that Eastman invented the name Kodak using a word game, but I prefer the idea that ‘Kodak’ mimics the sound made by the shutter, ‘click click’, ‘Kodak’. Moving images followed, then colour images, autochrome, gum bichromate prints created with three layers of light sensitive emulsion. The first world war saw the demise of many of the photographic processes of the 19th century, and for most of the 20th century the silver bromide gelatine based photographic materials have prevailed, but we still use chemistry that William Henry Fox Talbot would recognise in film and paper processing today.

The cave became the camera obscura, the dark ‘room’ used in the 15th century, shrinking first to a wooden box in the 19th century, then a tiny space behind the lens in the miniature cameras of the 20th century, and now in the 21st century a virtual space, an electronic image, created with a lens, but the camera, the ‘room’, no longer real. Even the metallic click of the shutter on the cameraphone is a gratuitous noise, there is no shutter to click.

There is still one mystery; Why did it take so long to capture the image first seen in the cave?

Some Cartes de Visite from the Morrab collections

Some Cartes de Visite from the Morrab collections