by Lisa Di Tommaso | Jul 29, 2021 | Blog, Images, Photographic Archive

This blog comes from one of our dedicated team of volunteers who work in the library’s Photo Archive. David and his colleagues are the people who scan and provide context to the thousands of images that end up on the Photo Archive website ( http://photoarchive.morrablibrary.org.uk/ ), available for you to peruse and enjoy. David has given us a brilliant insight into his role as a volunteer, but also reveals his brilliant piece of detective work in identifying one particular image – an act of perseverance and detective work which would put Sherlock Holmes to shame….

I volunteer in the photo archive as part of a team and see this as a great privilege to work in this wonderful library. This work is like no other; there is no pressure other than to carry out the task with great care, archive many photos, negatives and slides so that they are preserved forever. Preservation sleeves are used to protect them before they are put into conservation boxes for storage.

The room that I work in is new with views across the gardens – a lovely environment. As I sit at my desk, I have a PC and a scanner which must talk to one another if the photo is to arrive in its place in the digital collection. Once logged on then the process begins. This involves allocating a collection number to the photo before it is scanned. The computer programme allows me to add the data such as description, date, location, name of person or group. If it is a ship then the name and date is useful information. A facility also allows me to pinpoint the location on a map if known.

This is the easy part if the information pre-exists but often the process involves searching like a detective to identify the aforementioned essentials. I use books and the internet but there are also many photos in albums which have information about places and dates. All of this takes time but is very enjoyable. If the photographer is named then a search can provide interesting information about their work which is then added.

Fashions in clothing are always changing and it is interesting whilst compiling a collection, to note how fashion changed from the Victorian age and into the Edwardian era. Clothing becomes lighter and less dark and heavy. Women must have found life much easier. It is fascinating to find a detail written on the back of a photo, perhaps a date or a message to the recipient often encountered.

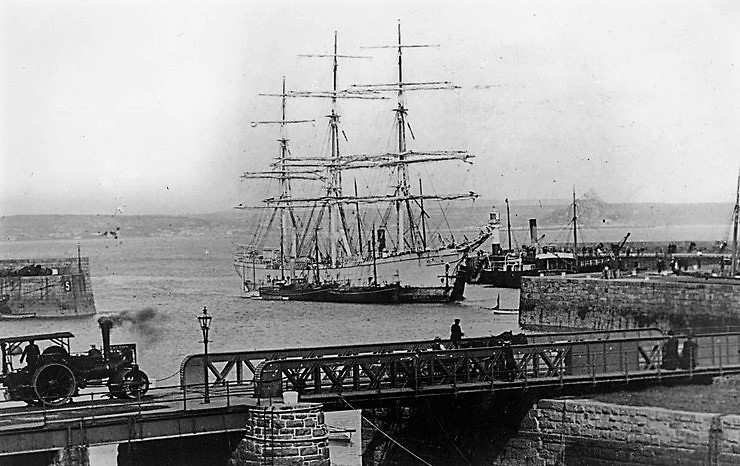

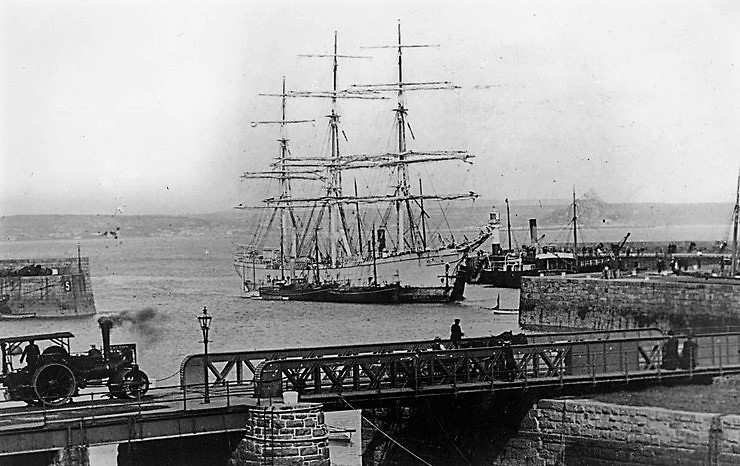

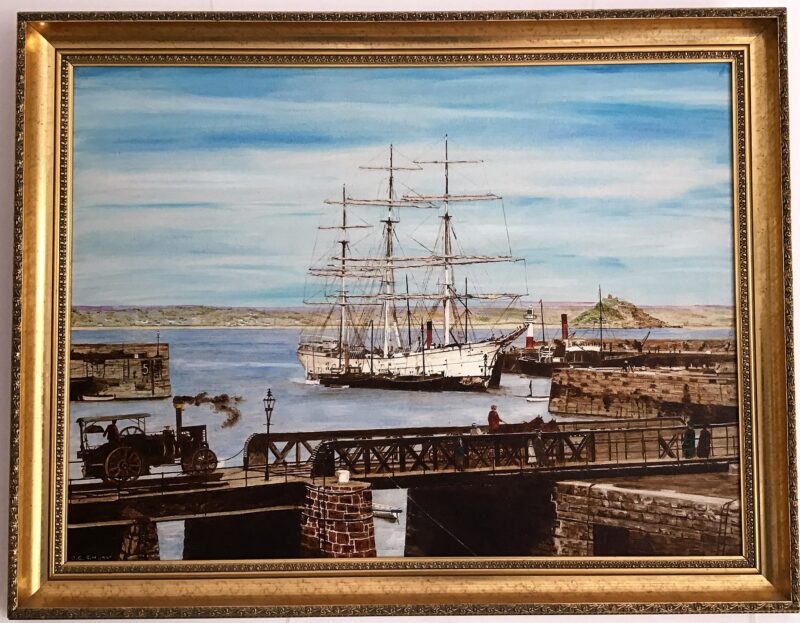

Currently I am working on a collection of miscellaneous photographs which are quite small, in an album with no information whatsoever. I had two photographs of a ship which, through using a magnifier I was fairly sure was in Penzance moored along the quay and the same ship in another photo moored alongside buildings. I needed to find out about this ship so I spent time at home searching for three-masted cargo ships with a white hull. Eventually I found information which identified it as the Leon Burau shown below. Using a magnifier, I identified the ship from the rigging and the shape around the bow. The additional information about the ship was then added to the data page, which will soon appear on the record accompanying the image on our website. Its story is fascinating and a summary follows below.

Morrab Library image: HARB 14HF 053

On the 18th of June1909 Alfred Vingoe was returning to Penzance in his pilot boat when he noticed that a large sailing ship was low in the water and flying distress flags. He and his two crew members sailed over to the craft which was the “Leon Burau” to find that the ship had been holed on a rock off the Scilly Isles and was fast taking in water. Climbing aboard Alfred told the captain to put on full sail, and when this was done Alfred piloted the ship into Penzance where he beached her just outside the harbour. The next day was a Sunday and people were amazed to see this fully rigged sailing ship ashore just outside the harbour entrance. Alfred arranged for most of the cargo to be discharged into small ships and then at high tide the ship was towed into the harbour to be repaired. A full account of the rescue is given in the “Cornishman” newspaper.

I was then able to identify that the ship in my photo was moored opposite what is now the dry dock in the harbour.

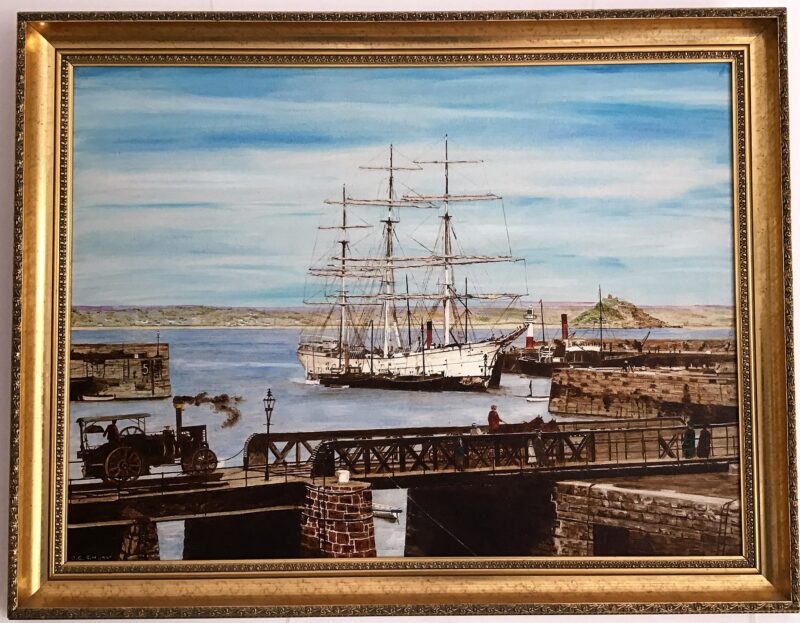

Just to add more interest an unidentified painting of this ship hangs in the photo archive painted by the Morrab Library benefactor Denis Myner. Further research identified the painting from an original photo as being part of the Richards collection. I then added the information to that photo on its web page identifier.

Painting by Denis Myner.

This is just one example of identifying a photo.

At the end of the day, I am usually left with a feeling of satisfaction in having made good progress but also knowing that many interesting searches lie ahead.

David Sleeman

If David’s blog has inspired you to consider volunteering with us in the Photo Archive, please get in touch with the library. You can email photoarchive@morrablibrary.org.uk or call the library on 01736 364474.

by Lisa Di Tommaso | Jul 17, 2021 | Blog, Uncategorized

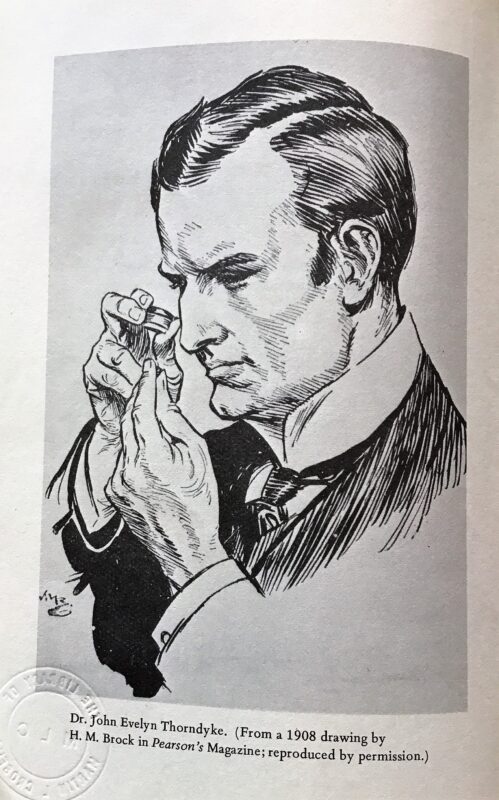

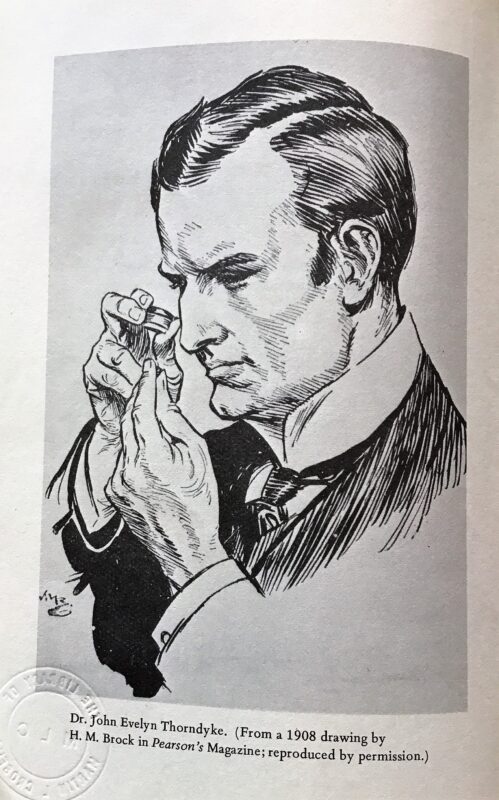

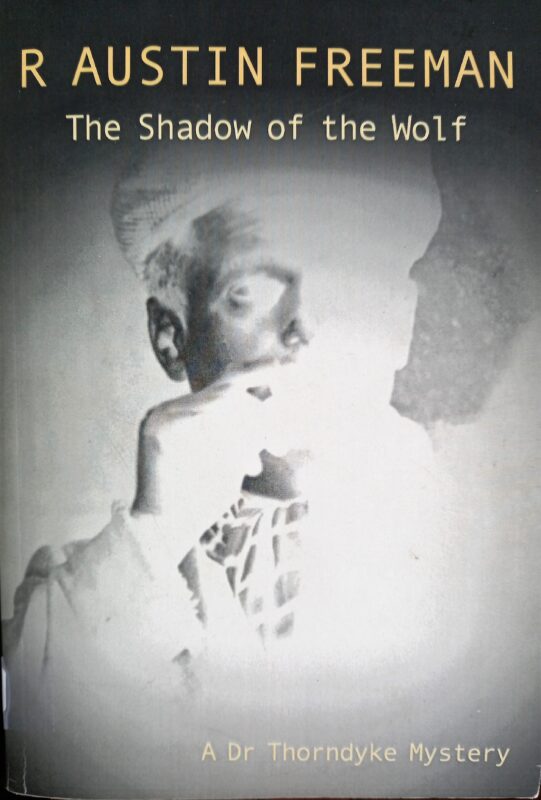

Dr. Richard Austin Freeman (1862 – 1943) was a British writer of detective stories, very much in the style of Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes. Library member Martin Crosfill has written a fascinating insight into the author and his character, Dr John Evelyn Thorndyke.

Dr Thorndyke: The First Professional Forensic Pathologist in Fiction?

On the Cornish fiction shelves is a book entitled “The Shadow of the Wolf ”. It is of interest partly because the action is centered around Penzance and the Bishop Rock Lighthouse, partly also because it is the first ‘inverted’ detection story. The identity of the murderer is revealed early on and the meat of the tale is concerned with the process of detection. Here is a short outline of the author’s life and work. The argument that the laurel belongs to Sherlock Holmes will be welcomed and challenged.

Click here to read Martin’s blog….

by Lisa Di Tommaso | Jul 3, 2021 | Blog, Morrab Library

Morrab Library has welcomed a new intern in the last few weeks. Eliza McCarthy is an English Literature student at the Penryn campus of Exeter University, who have funded Eliza’s project through their Access to Internships programme. Halfway through her time with us, we wanted to share how Eliza’s research is progressing, and her thoughts on the library so far….

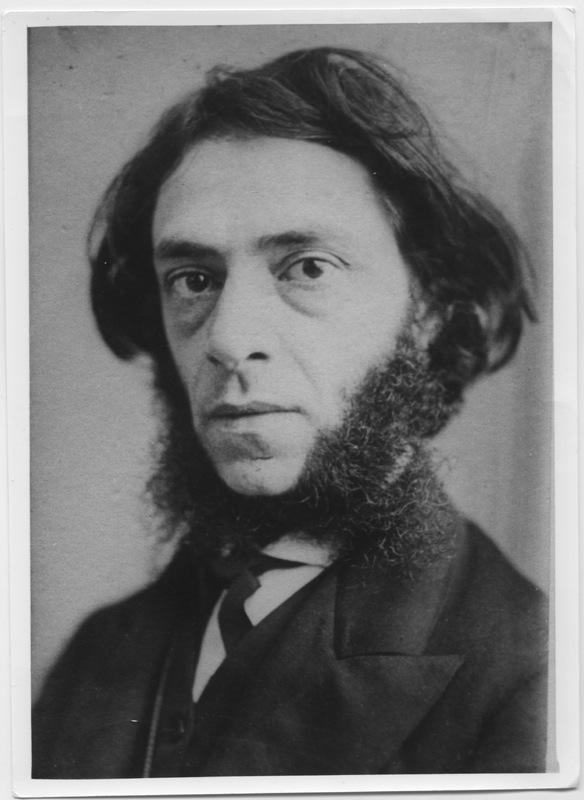

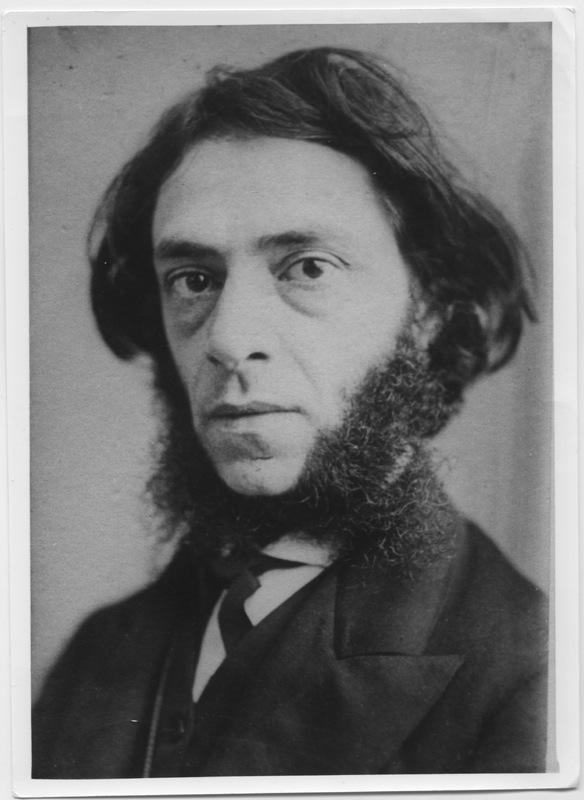

Over the course of the last month, I have been working with the extensive archive at Morrab Library on John Thomas Blight. The prolific artist and archaeologist is a familiar face around the library (his portrait hangs on the wall just outside the loo) and it has been a great pleasure to work so closely with a collection so integral to the rich history of Morrab Library.

The archive contains incredible diaries from his time at St Lawrence’s asylum in Bodmin, letters to friends and contemporaries, intricate line drawings and pages of rough sketches of sites across Cornwall. Looking through the archive, it is jarring to see such obvious evidence of Blight’s gradual downfall. His earlier sketchbooks contain countless rough sketches of familiar sights throughout West Penwith, drawings of local wildlife which are exquisitely detailed (my favourite being a small seagull, captioned ‘Little Bustard’. Clearly they’ve always been a nuisance). The later diary entries from Blight’s time at St Lawrence’s are just as detailed despite the fact his world suddenly became much smaller, with meticulous portraits of the faces of those confined alongside him, the interior landscape of the hospital, a rug, the bedframe, the heel of his newly darned sock…

It is very evident from Blight’s work, his profound, but sometimes entirely nonsensical musings crammed into tight corners of small notebooks (there must have been a paper shortage) that he so desperately wanted to leave an impression behind him, to be remembered like some of his more privileged contemporaries. Ironically, he was silenced and forgotten about within his own lifetime, swallowed by the social stigma that surrounded his poor mental health.

Of course, Blight’s somewhat sad story is well known by many of the library community. However, the goal of this project is to inject a little life into the archive, culminating in a research project that will explore some lesser known areas of the Blight story which perhaps deserve more academic attention than they initially received. I want to delve a little deeper into Blight’s time at St Lawrence’s Hospital, using his story as an anchor to Morrab Library whilst exploring the wider topic of the treatment of the ‘mad’ in the 19th Century, and what it meant on a social level to be deemed insane.

A huge thank you goes to Morrab Library for letting me come in and (gently) rifle through this incredible collection of work, and to Lisa for supplying me with chocolate and various other delightful confections whilst I do it.

by Lisa Di Tommaso | Mar 26, 2021 | Blog, Morrab Library

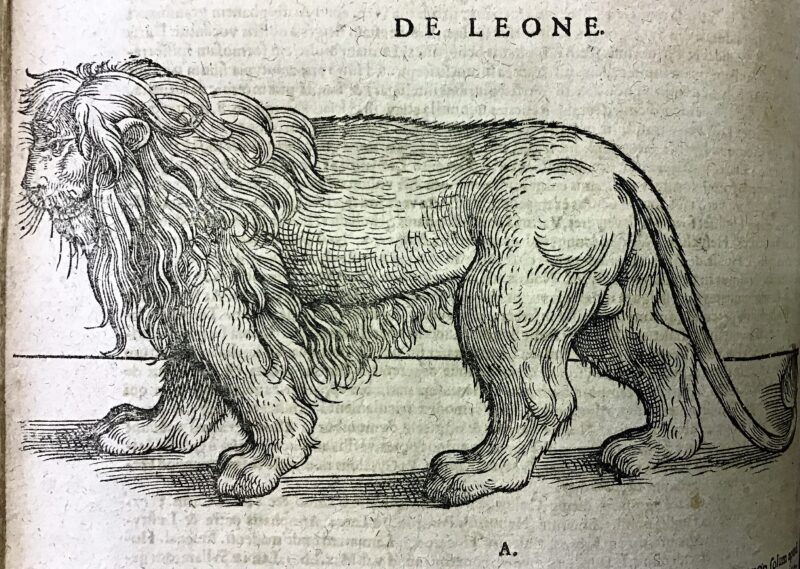

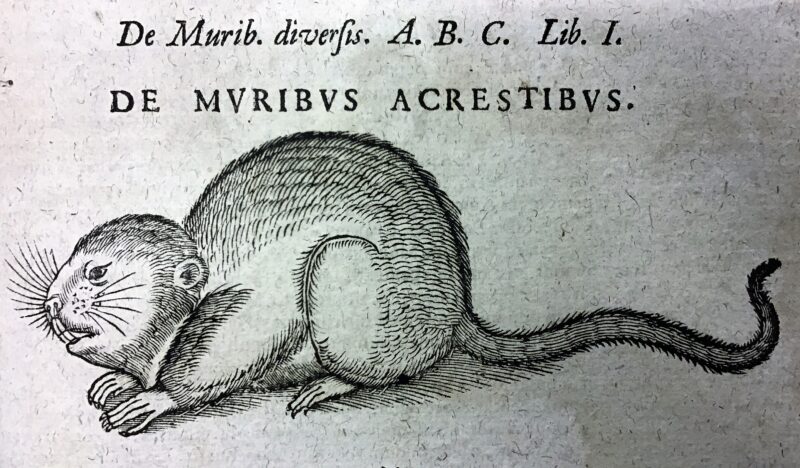

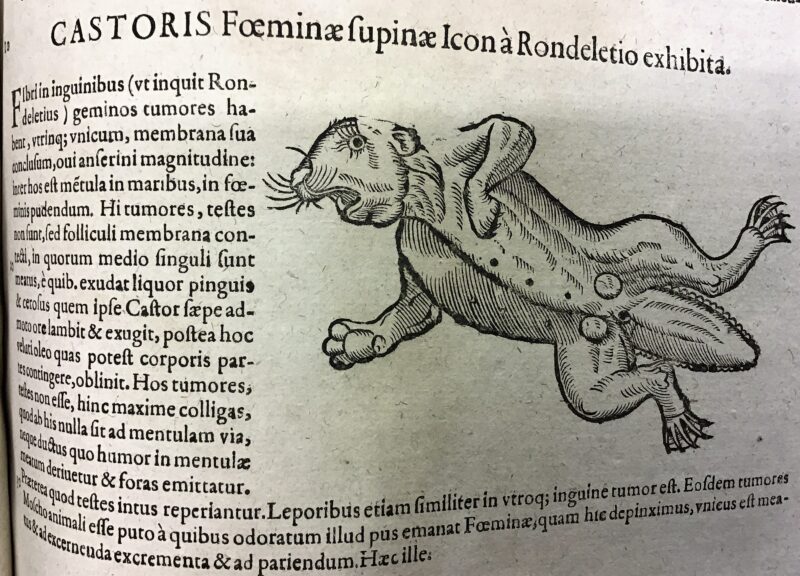

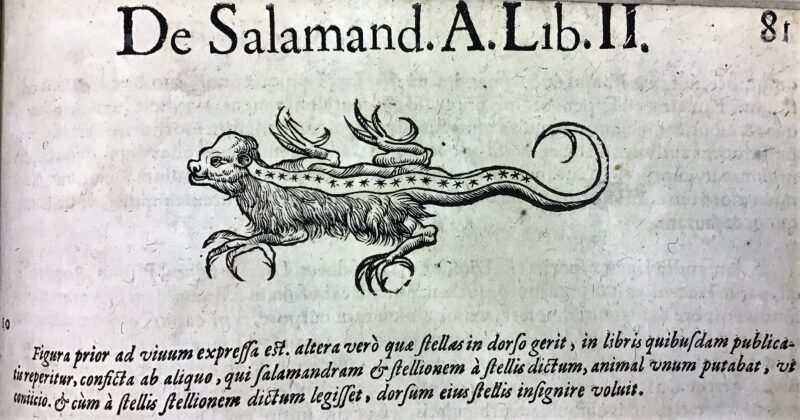

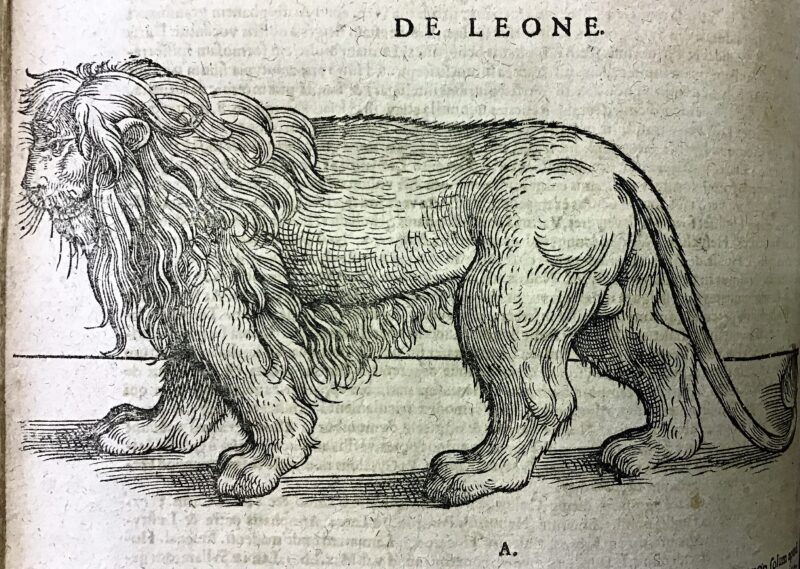

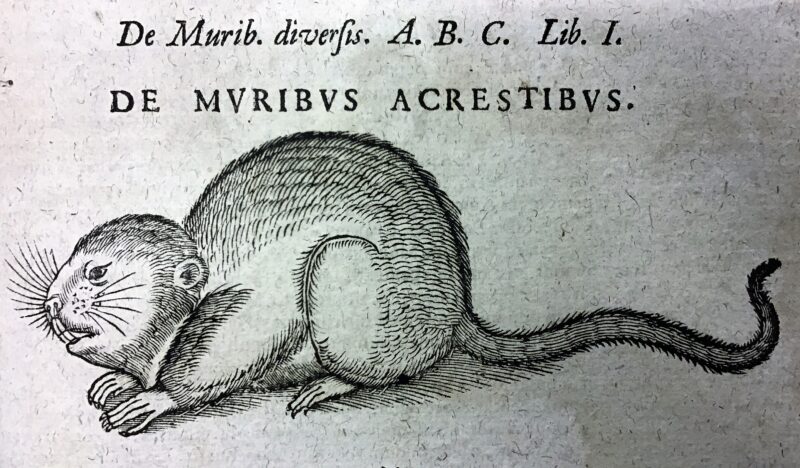

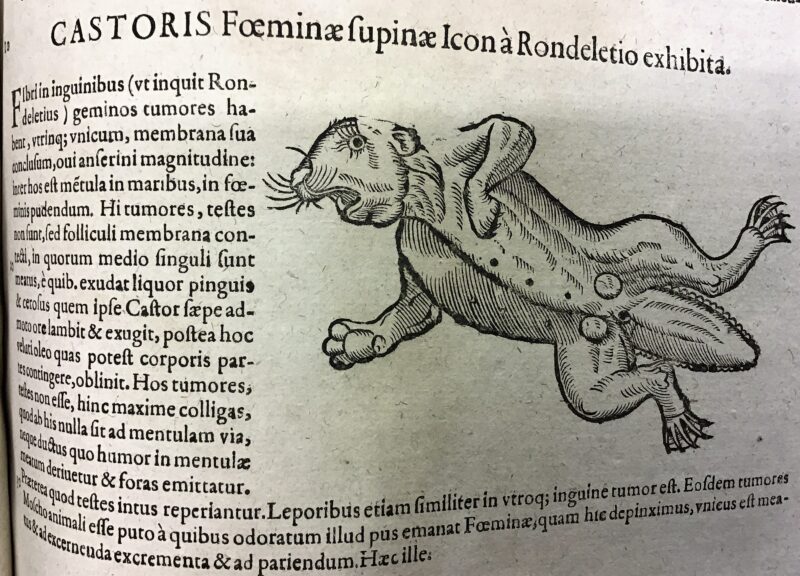

Humans have been drawing what they see of the natural world for over 40,00 years. Initially capturing images on rocks and in caves, this evolved over many centuries into hand drawn depictions and written descriptions being recorded in manuscripts. The development of the printing press in the 15th century changed everything – it was the first time mass produced books, complete with images, could be disseminated to a far wider audience than ever before. This, alongside developments in shipbuilding which allowed further travels afar, generated enormous interest and a huge demand for knowledge about the natural world beyond people’s own geography.

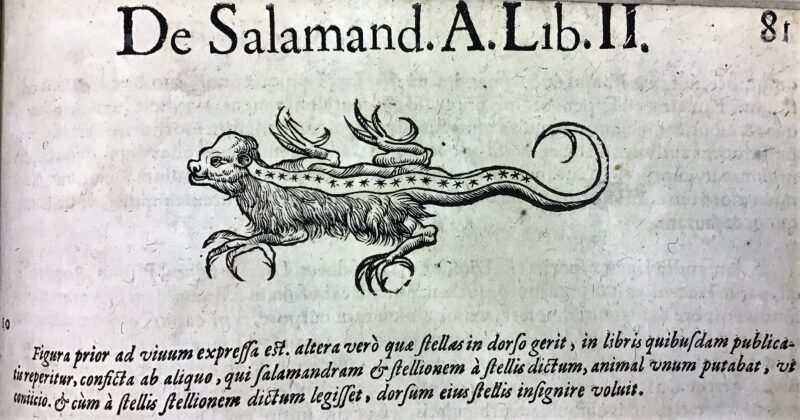

This period heralded the time that the science of natural history emerged, when many naturalists tried to make sense of the world, studying, collecting and classifying species and publishing compendiums and encyclopedias. This was also still a time when people accepted myths, legends and monsters as reality, so it was not unusual to believe in both science and the existence of dragons and unicorns.

Many published naturalists at this time didn’t travel far. Instead they relied on (sometimes distorted) descriptions of animals that fellow travellers and explorers had seen in order to create an image. As a result, depictions of animals weren’t always entirely accurate, and mythical creatures such as satyrs, hydras and sea monsters were often to be found depicted in the pages between horses and geese. They couldn’t prove that the creatures described didn’t exist, and there was no David Attenborough on hand to tell anyone otherwise, so everything was included. For example, many sailors told of amazing sea creatures and mermaids on their journeys, but it must be remembered that fresh water wasn’t available and rum was the drink of choice onboard! They may well have just been exaggerations of quite normal, or now extinct, sea creatures.

One of the earliest published naturalists was Conrad Gesner. A Swiss national who rarely travelled far and who died from the plague at the age of 49, he published widely on a number of subjects. His magnum opus however was the five volume Historia Animalium (1551-1558), comprising more than 4,500 pages of images and descriptions of all known creatures at that time. He combined information from his research of historic sources, such as the Old Testament, Aristotle and Pliny, as well as folklore and medieval bestiaries, with his own observations to create the first comprehensive description of the animal kingdom. Historia Animalium was also one of the first books to be illustrated with woodcuts drawn from personal observations by Gesner and descriptions from his colleagues. It was published in the two recognised scientific languages of the day – Latin and Greek.

The book wasn’t without its controversy. Pope Paul IV added Historia Animalium to the Catholic Church’s list of prohibited books. Gesner was a Protestant and the Pope felt that his faith contaminated his observations and writings.

The legacy of Gesner and other naturalists of his time cannot be underestimated. They were the people who established the basis of the science of zoology, classification and taxonomy – the first to try to categorise like groups of species together. Their drawing style and technique still influence the way scientific illustration is presented today. And the volumes provide an important snapshot into society’s knowledge, and beliefs of that time, where mythology and science were beginning to disconnect.

Morrab Library is fortunate to hold the first two of the five volumes of Historia Animalium in its collections. Our editions are dated 1617-1620, around 70 years after they were first published, and they are a very special treasure amongst our collections.

Lisa Di Tommaso, Librarian

by Lisa Di Tommaso | Aug 25, 2020 | Blog

In 2019, the Hypatia Trust’s Melissa Hardie launched her book – Bronte Territories: Cornwall and the Unexplored Maternal Legacy, 1760-1870. Melissa’s research reveals the often overlooked but important influence of the maternal family background on the Bronte sisters. The book delves deeply into the Cornish context and cultural understanding in which Maria (Carne) Bronte, her sister Elizabeth (Carne) Branwell and their family lived.

Morrab Library member and Trustee George Care has written a review of Melissa’s book, and it follows below. You will find copies of the volume to borrow or read here in the library.

Wandering down Chapel Street in Penzance, you cannot fail to recognise that you have entered that part of town where history feels close-by. The sea in the distance, the church and the chapel architecture is impressive, the Turk’s Head Tavern and the baroque wonder of the Egyptian House, the Portuguese consulate and almost opposite the house where George Eliot stayed waiting for calm weather for her voyage to the Scillies. Reading Melissa’s book is like taking a similar peregrination through lost corridors of time to recover a sense of the rich liveliness of Penwith’s past. Welcome to the psychogeography of Bronte’s Territories.

The Brontes are still much in the news. The Irish Times, just two weeks ago, were reporting on the O.U.P. computer analysis of Wuthering Heights apparently confirming it to be the work of Emily and not, as had been suggested, that of her brother Branwell. Iconoclasm may be in vogue. However, a square in Brussels – the city where two of the Bronte sisters studied French – is to be named in honour of the literary siblings. Other authors make claim to curious events in Shropshire in the early years of the 19th century drew the parents of genius together. It is to the intellectual and feminine furore of Penzance and its inspiring hinterland that Hardie’s work appropriately returns us.

In a key chapter on the literature and legend of Cornwall from 1760 much mention is made of the intriguing and taciturn figure of Joseph Carne, a geologist of great renown and an energetic banker. His personality was such that he combined a skill with numbers with a strong Methodist belief and mixed in a variety of literary circles. Nearby Falmouth was a key port for the Packet boats recorded in the poetry and memoirs of Byron and Southey. It too was the home of the Quaker family of Foxes who founded the Cornwall Polytechnic Society in 1832. Carne was a friend and shared their Non-Conformist beliefs. Hardie shows how Carne encouraged his daughter in her geological studies and mentions the doctors, engineers, vicars and scientists whose cultural sources were enriched by contacts which included Bretons, Huguenots, Hessians as well as a significant Jewish community. She reminds us that in reading Davy, for example, we encounter not just a socially beneficent scientist, a traveller and a poet. This is the endowment the Branwell sisters took to Haworth.

It is interesting to consider that within this Cornish background at this period there were a number of competing beliefs and attitudes. There were the mythical beliefs fostered from folklore- piskies and stories in the expiring Cornish language. There was the old religion of Rome not far beneath the surface. Yet there were also new discoveries especially in medicine and geology that fostered a scientific empiricism. This can be seen in figures such as Davies Gilbert to whom this book gives due prominence- a polymath, mathematician, engineer and President of the Royal Society and a wonderful diarist to boot. William Temple much later stated, “The Church exists primarily for the sake of those who are still outside it. It is a mistake to suppose that God is only, or even chiefly, concerned with religion.” It was the evangelical zeal of the Wesley brothers and their belief in education, temperance combined with stunningly beautiful hymns. It was also a challenge to superstition. It is often said it averted revolution which France and later Peterloo portended.

Melissa Hardie shows us the other supportive factors that came into this heady mixture and sustained the Branwells and flowered in the Bronte’s work. These are twofold; the societies and the family or kinship links. The Penzance Ladies Reading group who carefully studied together a stunning variety of literature from the classics of the Ancients to the contemporary travel writings. Not forgetting the subversive eloquence of Lord Byron, a gentleman with Cornish links through the Trevanions. The founding of libraries and collection of artefacts had practical even economic benefits. The Royal Cornwall Geological Society studies into metallic intrusions assisted the efficiency of mining. Local banks provided the capital for further developments in the industry as well as the magnificent Wesleyan Chapels that the Carnes, Branwells and Battens founded and fostered.

The author has researched both land and legacy extensively. Her approach is frequently imaginative and sometimes speculative. This is a strength because she is also at pains to inform the reader of the limitations of the evidence. Footnotes and suggested reading in themselves are useful but the illustrations are worthy of pondering- several works of art in themselves. They add significant detail. This patient work by Melissa supported by other members of the resplendent Hypatia Trust must be counted as filling a deep fissure, or as we might say in Cornwall, a zawn in Bronte Studies.

August 5, 2020.

–

The Elizabeth Treffry Collection on Women in Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly – a permanent gift to Morrab Library from Melissa Hardie and the Hypatia Trust.