by admin | Sep 13, 2019 | Blog

This blog piece was written by Library member, Jean Y. Jones.

A sunny morning. In Morrab Library I sat in my leather chair, book in lap, gazing out of the Georgian window over the gardens and out to sea. The library was quiet and peaceful. The book on my lap, taken from the shelves in the Cornish Room, was Daphne de Maurier’s Rebecca.

Manderley, the house of all our dreams, a country house of the kind familiar to us all through the medium of the novel. The link is astonishing. From its earliest inception as a literary genre, the novel has looked to the english country house for background and setting.

When Richardson considered using imaginative story-telling as a vehicle for his views and opinions he placed his heroine, Pamela, in the country house, a pretty servant faced with moral dangers therein. So successful was he that Smollett and Fielding rapidly followed in his footsteps. The country house proved a perfect background to exploit, for tales of high romance and derring-do, of Gothic mysteries and horror. Jane Austen, writing a while later, used the country house as a more conventional setting, with its beautiful parklands, grand rooms well-furnished and well-appointed, of the kind so highly admired by Henry James. With it came a way of life that over generations had evolved into a strong social class system, the English gentleman exhibiting an etiquette of manners, at times civilised in the extreme, exclusive and insular. Save for the imaginative incursions of the novelist.

So great was the attraction of the country house to literature that it moves frequently from background to foreground. In Pride and Prejudice Darcy might well have remained a bachelor were it not for Pemberley and its effect upon Elizabeth. Similarly, in Northanger Abbey Catherine is quite led astray by the house, almost as much as General Tilney was by rumours of her wealth.

The country house is used to a more passionate and vibrant effect by the Brontes – Wuthering Heights, brooding over the moors, Jane Eyre with its mad woman in the attic. Even Charles Dickens succumbed to its use, in Great Expectations skilfully creating in the mind’s eye the dark and deserted rooms leading ever inward to Miss Havisham’s wedding feast.

But with industrialisation breaking up the patterns of rural life, universal education and democracy, the tenor of novels shifted to the more social and political. Disraeli’s Sybil, George Eliot’s Felix Holt, the Radical, Trollope, concentrating on domestic dramas played out in the country house, closely followed by Galsworthy’s Forsyte Saga. All still using the country house and its social context to centre their narratives on.

As the twentieth century progressed, writers of a different mettle appeared, some, self-proclaimed self-conscious intellectuals like those of the Bloomsbury Group, products themselves of the country house epitomised in novels like Mrs Dalloway, Howard’s End and Brideshead Revisited. These gave way in turn to the novelist writing for a newer kind of reader, exploring a wider range of experience. Though still the country house maintained its allure as in D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover. Crime writers found it a great setting and jumping-off platform, as evidenced in Agatha Christie’s works, and Conan Doyle. This has persisted to the present day.

Its romance endures, in the charm of Georgette Heyer’s Regency works, in for example Catherine Cookson and Jilly Cooper’s writings, right through to contemporary fiction. And who can forget the superbly written “Remains of the Day” by Ishiguru?

The country house may no longer by the symbol of power, wealth and privilege it once was. Yet it lives on, in our novels, in our imaginations, and on the shelves of our own country house, Morrab Library.

by Lisa Di Tommaso | Aug 23, 2019 | Blog

A new book from the Penwith Local History Group

The Penwith Local History Group (PLHG) has enjoyed a strong relationship with Morrab Library for many years. The group undertake important and fascinating research into West Cornwall and are based here at the library, meeting regularly and making us of our collections.

Their latest book, Growing up in West Cornwall, follows a long line of important and valuable works by the PLHG. This is their 11th title, the first being published in 1990. Previous volumes have covered topics as diverse as farming, Cornish women, and the Naploeonic era, as well as highlighting the treasures of Morrab Library’s collections. A full list can be found on their website: http://www.penwithlocalhistorygroup.co.uk/publications/

All of the publications provide a detailed insight into their subject with evidence of extensive research, yet written in a thoroughly engaging style, making them accessible to a wide range of readers be it for academic use or just personal interest.

Growing Up in West Cornwall is no exception. As it says on the tin, it brings to life the experience of childhood in West Cornwall, from as far back as the seventeenth century, taking us up to the 1960’s. There are numerous fascinating illustrations and photographs throughout, which are invaluable in helping to tell the variety of stories that emerge from the pages. It combines the use of archival records such as school logs and parish records, alongside personal recollections from the contributors and people they have interviewed. There are also very extensive subject, school and surname indexes at the end, a useful bibliography, and excellent footnotes and references throughout – essential for researchers.

Growing up in West Cornwall talks of all aspects of childhood, including of course schooldays and playtime, but also work, when many children were expected to take up labour at such young ages, working with the fisherman, in the fields and even with the undertakers!

All sorts of fascinating stories have emerged – we learn that in 1600, boys from the age of 7 had to practise their archery in the Zennor churchyard, and that all young men from the age of 16 were obliged to bear arms. We are told of library books needing to be burnt after an outbreak of deadly measles in St Erth in 1917. And the stories about the bad behaviour of the boys at the Recreation Ground after it opened in 1893 prove that some things never seem to change!

For Morrab Library, the group’s ability and avidity in using the library’s collections of books, archives, newspapers and photographs to bring the stories of the events and people of West Cornwall to life is so important to us. The PLHG contributors’ hard work and research skills ensure that our collections remain relevant and interesting to not only our members, but the wider community, creating an awareness of them and encouraging others to make use of them. The Library looks forward to continuing its work with the PLHG in the future.

You can borrow a copy of Growing up in West Cornwall or purchase your own from the library’s front desk, at a cost of £10.

Lisa Di Tommaso, Librarian

by Lisa Di Tommaso | Aug 10, 2019 | Blog

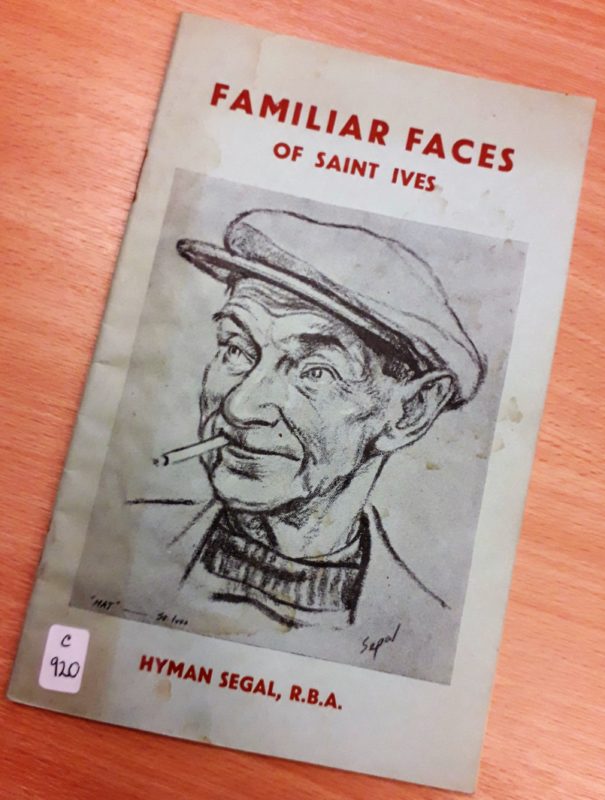

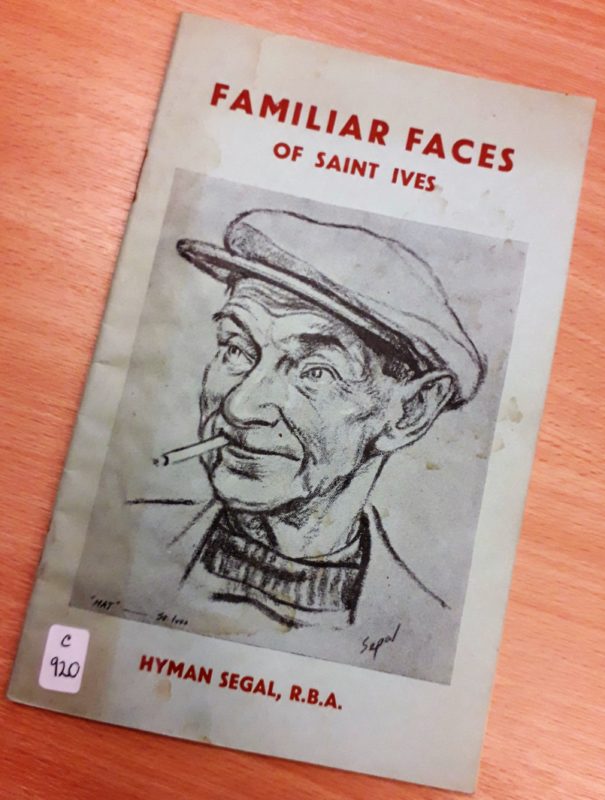

The library has recently received a charming donation. Titled Familiar Faces of St Ives, this uniquely illustrated pamphlet of around 20 pages offers a brilliant summary of life in St Ives just after the War – the town’s ‘Silver Age’ it might be termed. This fascinating time period is manifest in the vivid sketches by the well-known St Ives artist, Hyman Segal. https://cornwallartists.org/cornwall-artists/hyman-segal

Segal is probably best remembered for his African paintings as well as for his skill in portraying cats with sweeping economical lines. A Daily Mirror photographic frontispiece shows him, an Art Therapist at West Cornwall Hospital, helping the recovery of a young lad at Tehidy Sanatorium in Camborne. This classic photograph by Bela Zola indicates the pride in the newly created NHS (Zola was a leading photographer who recorded later the Aberfan Disaster and the Profumo Affair among other renowned assignments.) https://www.worldpressphoto.org/collection/photo/1956/28663/1/1956-Bela-Zola-GN1-(1)

The first sketch in the pamphlet is of our celebrated Town Crier, Abraham Curnow – here just 54 years old. This is accompanied by a sketch of his Father-in-Law, Ernest James Stevens, popularly known as “Jimmy Limpets”. This drawing with others by Segal now hangs in the Sloop Inn.

On the following page is an image of Thomas Tonkin Prynne who had been the manager of Lanham’s picture framing business which in previous years supplied the Royal Academy and other galleries with canvases by inter alia , Julius Olsen, Louis Grier and Moffat Linder. In addition to running an efficient business, he worked for 16 years as a member of the volunteer fire brigade, had a blue Persian cat and loved fishing.

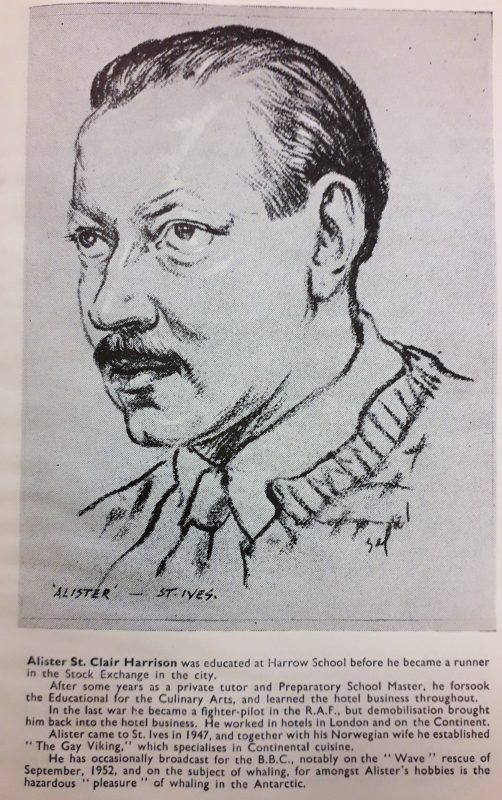

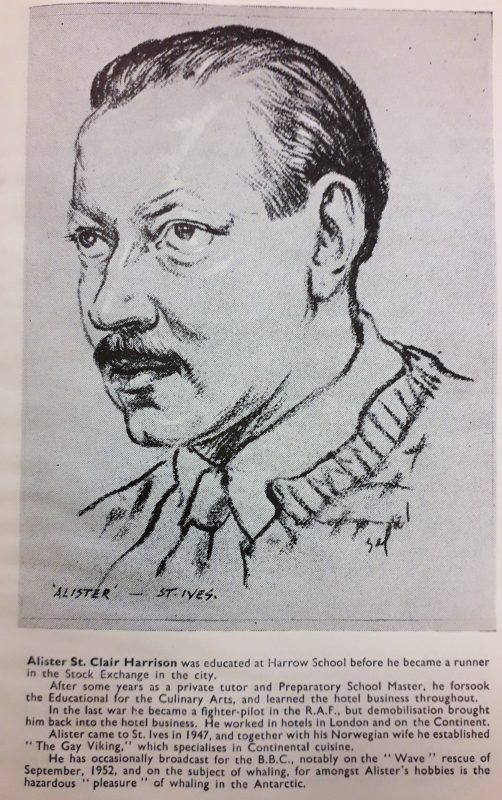

There is also a magnificent sketch of Alistair St Clair Harrison, like Churchill, an old Harovian who had been a fighter pilot during the Second World War. It was Harrison who broadcast for the BBC about the rescue of HMS Wave in September 1952 and also about his interest in Antarctic whaling. It was with his Norwegian wife that he established “The Gay Viking”; almost as famous for its colourful clientele as its innovative continental cuisine. (Gay Viking was incidentally one of eight vessels that were ordered by the Turkish Navy, but were requisitioned by the Royal Navy to serve with Coastal Forces during the Second World War).

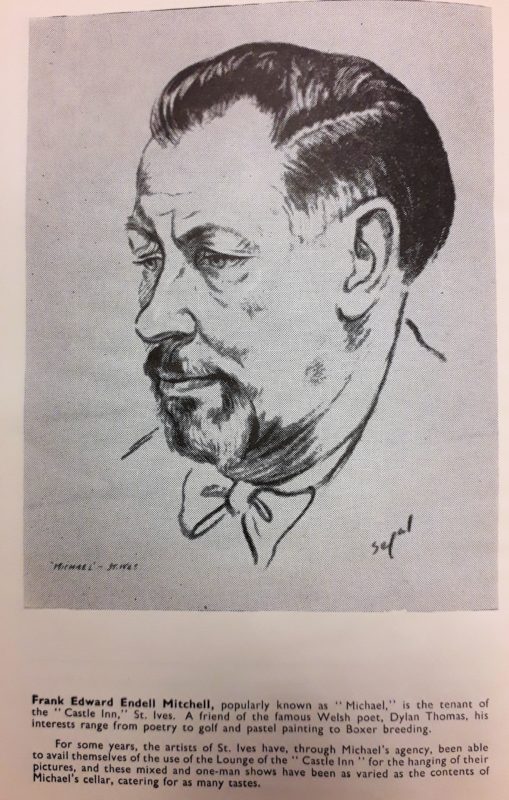

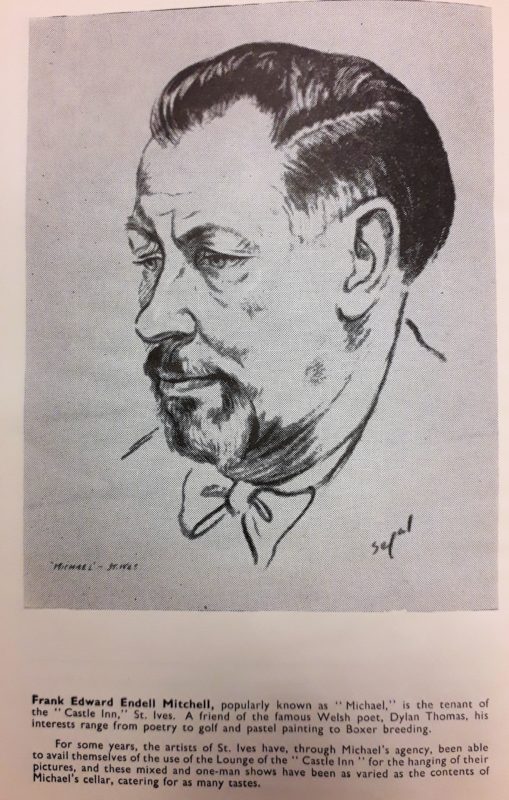

Frank Edward Endell Mitchell, appropriately portrayed with bow-tie, fashionable in the 1950’s, was known as “Micheal” and was the tenant of the Castle Inn. His friendship with Dylan Thomas must have been firmly established in the bohemian atmosphere of the bar there, then opposite Lanham’s and the Scala Cinema (presently Boots). Mitchell, who was the brother I believe, of the eminent sculptor, Denis Mitchell, offered the Castle lounge for the display of art works and in his spare time, he himself did pastels and was occupied in breeding Boxer dogs.

The donation of this little pamphlet to the Morrab Archive offers members the opportunity to recreate for themselves the ambience of the Fifties through “The Familiar Faces of St Ives”.

George Care, Library Member and Trustee

by admin | Jun 28, 2019 | Blog, Morrab Library

This book review is by our member Ned, aged 9.

Mr Gum & The Dancing Bear by Andy Stanton (part of the brilliant Mr Gum series!)

It’s about a bear called Padlock who comes strolling into the little town Lamomic Bibber. The bear has beautiful hazlenut eyes and shimmering golden fur. But the bear wasn’t happy. He was lost. Then polly came to the rescue. But where was Mr Gum and old Billy? Well, they were in Billy’s rancid butcher shop playing a game called The World Champion of the Butcher’s Shop lying contest. Read the book to find out more about Mr Gum and his terrible plans…

I liked this book because –

- The drawings made me laugh.

- The bear’s sadness made me sad.

- It was bizarre.

- It was funny.

- The last bit made me happy.

- The most funny bit was the measurements: as tall as 40 hamsters and as heavy as 19,000 grapes (the bear, not Mr Gum).

by admin | May 22, 2019 | Blog, News

A hidden treasure revealed

By Tehmina Goskar

Song of the Chough

Black is the Chough’s colour,

Red are its singing beak and legs,

Still alive on Cornish cliffs,

Although people say it is dead.

He is not dead,

He is not dead,

King Arthur is not dead!

This is the translation of a remarkable Cornish song found tucked away in the Jenner Room in the Morrab Library. While examining the music pamphlets drawer for something completely other, I came across two slips of paper in an original copy of Dr Ralph Dunstan’s Cornish Dialect and Folk Songs, 1932. One is a letter from Dunstan to Henry Jenner, father of the Cornish language revival and founding bard of Gorsedh Kernow. The other is a beautifully penned musical manuscript of a song called Can Palores (Chough’s Song) composed (or arranged) by Dunstan. The book was inscribed by Dunstan to Jenner, dated 16 July 1932.

Dr Ralph Dunstan was born in Carnon Downs on 17 November 1857. He learned to play the bassoon, violin, organ and more. Dunstan became a music teacher at Westminster Training College and won a doctorate from Cambridge. He published widely on the theory of music and in particular composition and harmony. Dunstan was also a Cornishman, alive during an incredibly vibrant period for the Celtic-Cornish movement that saw the establishment of the first Old Cornwall Society in St Ives in 1920, the Federation of Old Cornwall Societies in 1924, and Gorsedh Kernow in 1928. He spent his retirement devoted to Cornish musical matters.

The musical manuscript found at the Morrab is fleeting, barely 12 bars long. It is scored in D major and seems to be arranged for harmony singing—arrangements familiar to those who have studied Dunstan’s other arrangements of Cornish songs (see his Cornish Song Book or Lyver Canow Kernewek, 1929).

The last line of the refrain, ‘King Arthur is not dead!’ is a motto that we find on some Cornish language publications of this period and it appears with a chough in the middle forming an emblem. The imagery and the words are tied up with the Cornish lore of King Arthur whose soul is said to reside in a Cornish chough.

Robert Morton Nance, a key protagonist of the Cornish movement, and a correspondent of Dunstan, used this emblem on several of his pamphlets. Dunstan himself became deeply interested in Arthurian ballads when he moved back to Cornwall.

Its single verse, in the style of Cornish that was being used for the language revival in the 1920s, suggests there were others. A search in the newspaper archives gives us an intriguing clue as to what this song might have been used for. The Western Morning News of 17 September 1932 contains an article by a correspondent called Cornishwoman. It describes a Celtic song, dance and theatrical concert performed at the Royal Institution of Cornwall, Truro under Dunstan’s direction.

The article refers to a Cornish interlude called An Balores (the Chough) in which Phoebe Nance took part. Phoebe Nance (Morwennol—Sea Swallow) from Carbis Bay was made a bard of the Gorsedh the week before. Could it have been Phoebe that performed Can Palores during her interlude? The evidence is compelling. In the same year, 1932, Robert Morton Nance (Mordon) – Phoebe’s father –published a short play called An Balores and it ends with a three-verse song that finishes with the refrain, “Nyns yu marrow Myghtern Arthur!”

The letter, dated 18 July 1932, leaves a clue to the vast collection of unpublished material that Dunstan said he still had in his possession. “I have many other Cornish Songs of various kinds – several from Jim Thomas — I see no hope of ever publishing them in complete form with accompaniments.” Jim Thomas was a massively important figure for Dunstan during his collection of Cornish music and song of the type that took place in village halls, at chapel tea treats and mostly, in pub sessions up and down the Duchy. He goes on to describe the kind of book he would have liked to have published next, a Pocket Companion of Cornish Songs, and what would be in it. The letter itself does not refer to Can Palores.

Ralph Dunstan died on 2 April 1933, not long after writing the letter to Henry Jenner, and his Pocket Companion was never published. Dunstan’s own personal archive was apparently either burned by his daughter after his death or according to another report, left to go damp in a garden gazebo. Whichever is true, these two original survivals become all the more precious.

Can Palores

An Balores du hy lyw,

Ruth ha’y gelvyn can ha’y gar-row,

War als Ker-now whath a vew,

Kyn leverer hy bos marrow.

Nyns yu marrow,

Nyns yu marrow,

Nyns yu marrow Myghtern Arthur!

(Translation above courtesy of Cornish Language Office, Cornwall Council).

For information on interpreting the music and understanding Ralph Dunstan’s context, our sincere thanks to:

– Merv Davey, Folk Songs & amp; Music Recorder, Federation of Old Cornwall Societies

– Anna Dowling, Violinist, Singer and Composer

– Steve Penhaligon, Keur Heb Hanow

– Karin Easton, Perranzabuloe Museum and President of Federation of Old Cornwall Societies

– Pol Hodge, Cornish language scholar and poet, Golden Tree Productions

Tehmina Goskar, May 2019. For correspondence: tehmina@goskar.com

by admin | May 11, 2019 | Blog

This fascinating piece was written by Martin Crosfill, a member and life long supporter of the library.

Browsing, as one does, among the shelves of the Morrab Library, I came across a book entitled “Aristotle’s Masterpiece” and, inside, the “Works of Aristotle”. As I had seen a copy of these works in twelve large volumes, and as this one was only five inches high, something seemed odd. It turns out that it is one of a number of Pseudo-Aristotelian writings and is, in fact, a sex manual. The title was possibly used as camouflage, but the work became so widely distributed and so easily obtained that request for it was quite likely to elicit a knowing snigger from the bookseller.

It is, in fact, a remarkable book with a remarkable history. It was first registered at the Stationers’ Office in 1684 by John How, with the subtitle The Secrets of Generation and was an immediate best seller. The author is not recorded, which is fair in that it is a hotchpotch of material from many sources. It owes nothing to Aristotle except the name and a faint echo of his treatise de generatione animalium. Of more mainstream books there are Jacob Rueff (de conceptu et generatioine hominis 1554) and William Harvey (De Generatione Animalium 1651) but the strongest influence was probably from writers on domestic medicine such as Culpeper (Directory for Midwives), Lemnius (A Discourse touching generation 1664) and John Sadler (A Sicke Woman’s Private Looking Glasse 1636).

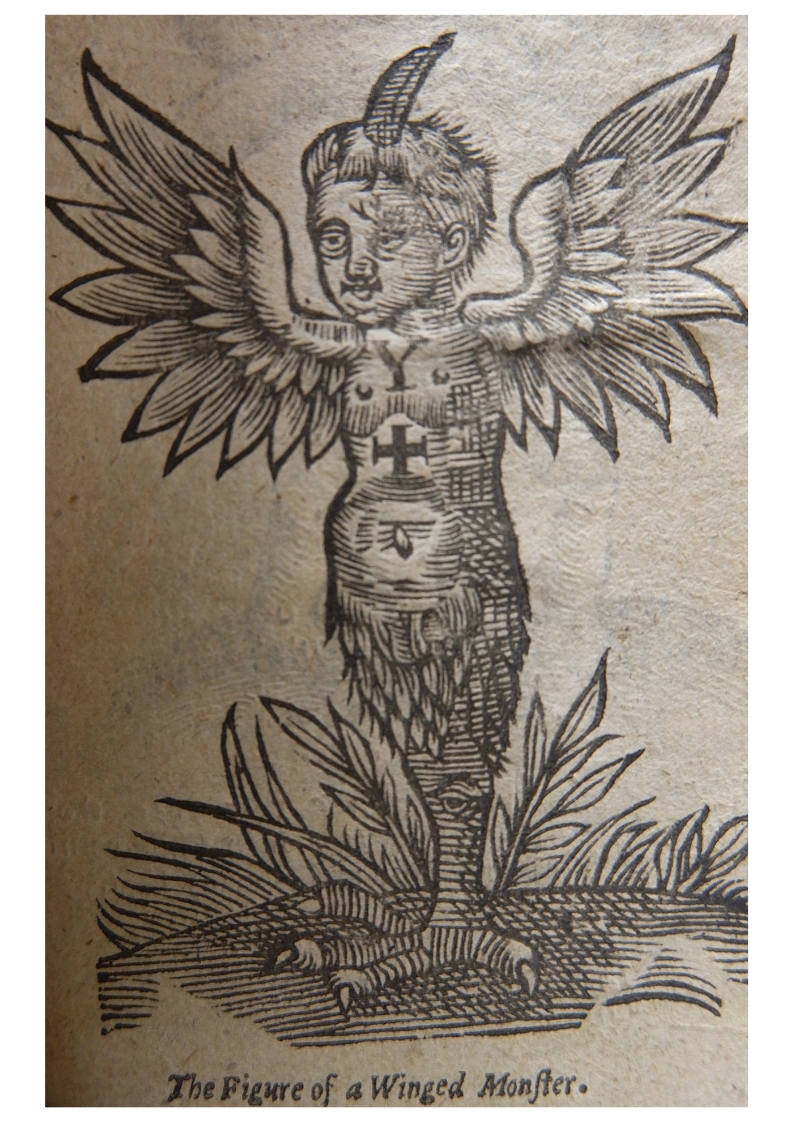

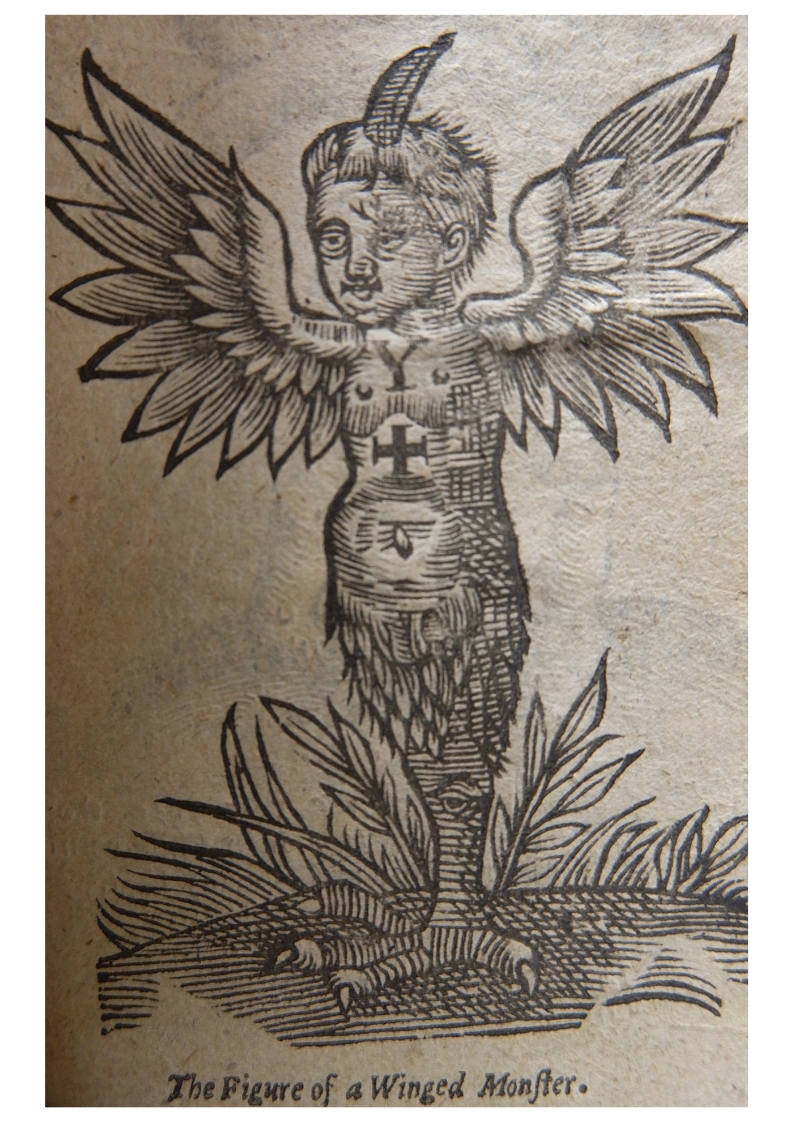

It would be fascinating to seek for evidence of plagiarism in the text of the Masterpiece, but it would be a mighty task; not so when the images are concerned – every edition I have seen is illustrated with woodcuts, mostly of monstrous births. I have attempted to trace one, the Ravenna Monster. His/her birth was recorded in 1512 contemporaneously by a Florentine diarist Luca Landucci, who described it from a drawing. “it had a horn on its head, straight up like a sword, and instead of arms it had two wings like a bat’s, and at the height of the breasts it had a fio on one side and a cross on the other, and lower down at the waist, two serpents, and it was hermaphrodite, and on the right knee it had an eye and on the left foot an eagle.” Such an image was too good to waste, and it soon appeared in books of monsters by Boaistuau (1560) Pare (1573) and Lycosthenes (1573). The second leg (and the eagle) were rapidly dispensed with. The monster appeared in the first edition of the Masterpiece and in almost all subsequent editions I have seen, up to and including the twentieth century century. The poor little creature deserves a posthumous fame. Pope Julius 11 ordered it to be starved to death.

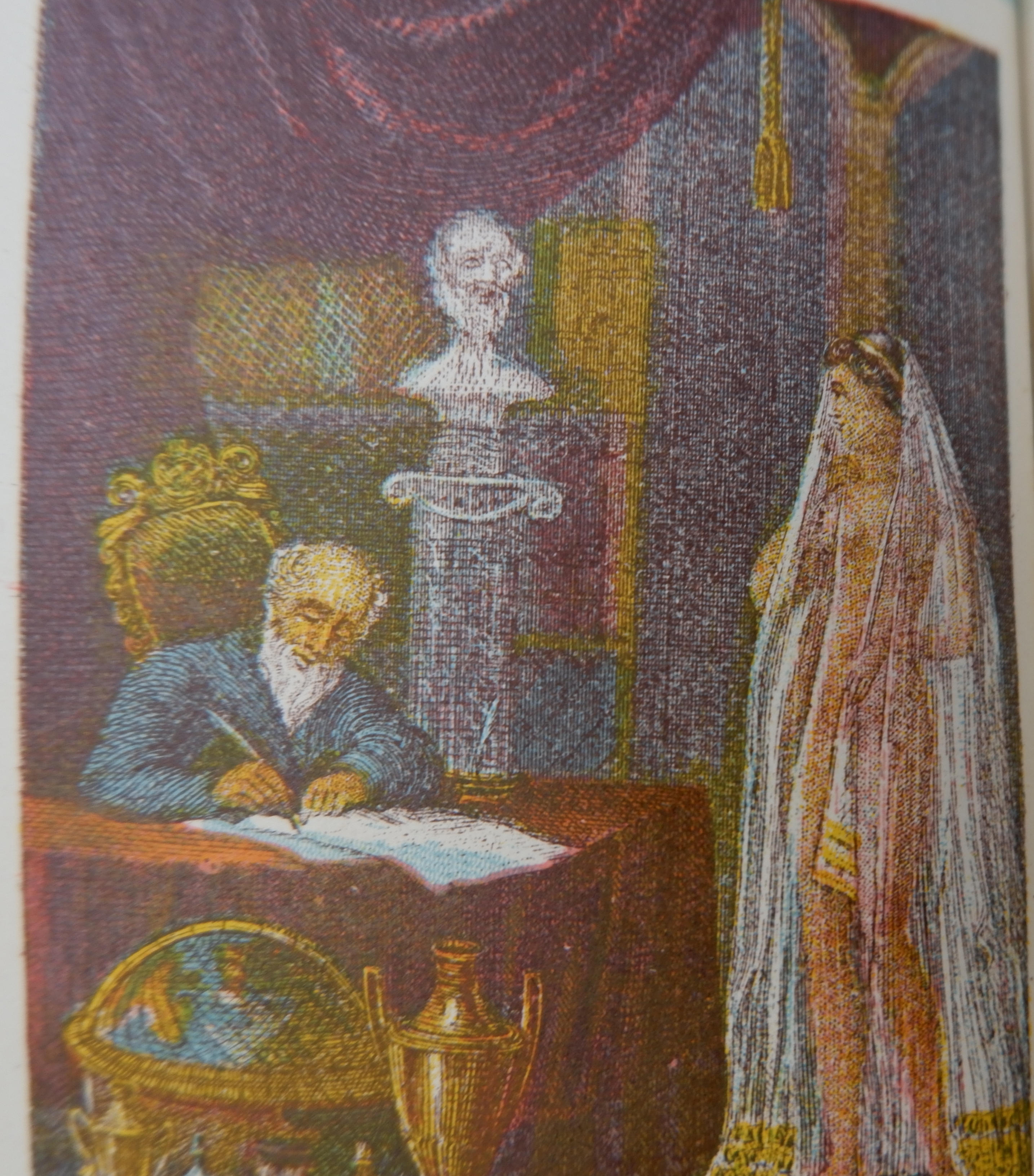

The earliest editions of the book start with the young maid. As soon as she reaches puberty (at fourteen or fifteen) she becomes ‘inclinable to marriage’. Parents are advised ‘not violently to restrain them, but rather to provide for them …. such husbands as may be for their advantage….lest, being crossed in their purposes and delayed, they part with their honour (in) dishonourable ways.’ In other words, they are up for it, but the ‘it’ for which they are ‘up’ is generation, the procreation of children within the bounds of wedlock. The male, it appears, may not be so enthusiastic – ‘the appetite and desire to copulation, which fires the imagination with unusual fancies, or by the sight of a brisk charming beauty, whose wit and liveliness may much incite and more inflame the Courage: but if Nature be enfeebled then are fit Artificial Remedies to restore it.’ There follows an intriguing and comprehensive list of aphrodisiacs. After copulation, the woman must lie on her right side if she wants a boy, on the left if a girl. Next comes an account of the conception and development of the foetus and an interesting section on the time at which the soul is ‘infused’ into the body; this turns out to be around 45 days. There are chapters on the choice of a midwife, on the conduct of the pregnancy and a little on the manipulations of the birth itself, a detailed description of the female genitalia may have helped sales, as may a section, reassuring for both sexes, which states that virginity is not incompatible with an intact hymen. At last, before the chapter on monstrous births, a word of advice to both sexes on the art of copulation “it is convenient ….to cherish the body with generous Restorative, to charm the Imagination with Musick, to drown all cares with good Wine; that the Mind being elevated to a pith of Joy and Rapture, the sensual Appetite may be more freely encouraged to gratifie it self in the Delights of Nature.”

Some eighteenth century editions are almost a complete rewrite. My 1749 copy starts straight off with a description of the male genitalia and the author is enthusiastic enough to burst into verse:

And thus man’s noble parts described we see

For such the parts of Generation be;

And they that carefully surveys, will find

Each part is fitted for the Use design’d

The female parts come in for similar treatment, after which:

Thus the womens secrets I have survey’d

And let them see how curiously they’re made:

And that, tho’ they of different sexes be,

Yet on the whole they are the same as we:

For those that have the strictest Searchers been,

Find Women are but men turned Out side in:

And Men, if they but cast their eyes about,

May find they’re Women, with their Inside out.

The book covers much the same ground as the first edition, with the same insistence on copulation within wedlock, but the treatment is altogether more knowing and satirical. It also illustrates the other characteristic of later editions, that of accretion. My copy has acquired a section on physiognomy, followed by “The Family Physician” (take a man’s skull, prepared…). Next comes the “Book of Problems”, a series of questions and answers which has a much longer pedigree than has the Masterpiece itself, and finally “The Experienced Midwife” and “His Last Legacy”. The Midwife, which occupies 150 pages, is an account of how to conduct a birth, comprehensive enough to explain how to remove the head after it has become detached from the body. It is interesting to find that, when things are really desperate, the she becomes a he, heralding the rise of the man midwife.

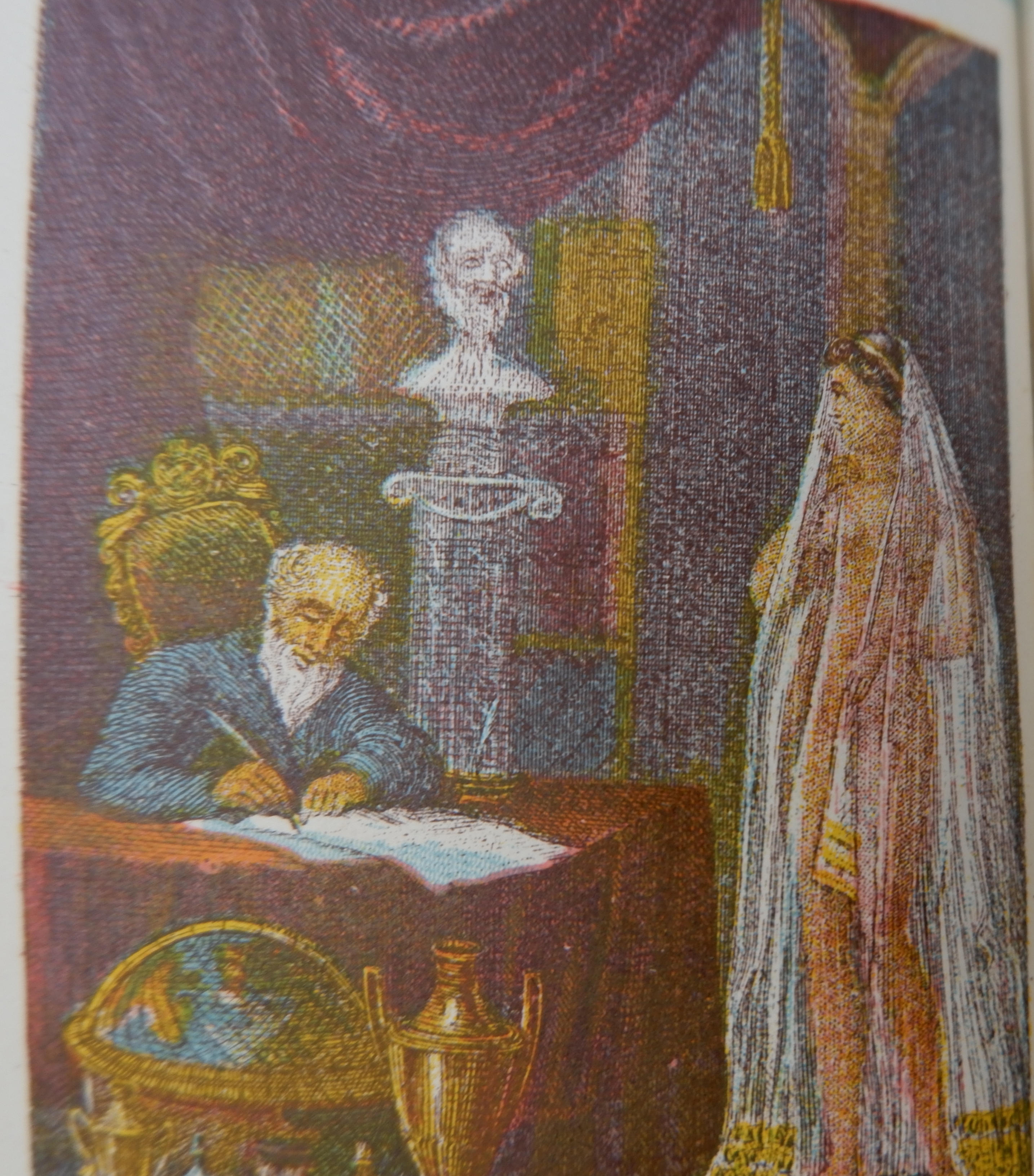

The rather racy tone and the tendency to lapse into doggerel verse persist into the early nineteenth century. The atmosphere then changes; the Masterpiece now starts with the section on conception, marriage and the infusion of the soul, burying the description. of the genitalia deeper in the text. I find it interesting that in none of the editions I have consulted is there the slightest suggestion of contraception, unless it be that among the treatments for stoppage of the periods are mugwort and pennyroyal – both abortifacients. The Library’s own copy was printed by John Smith of Tooly St, London and can possibly be dated to 1879. It contains crude chromolithographs of the development of the foetus, the wording is much more modern, but the medical advice looks back to the Galenical theory of humours. Of the ‘cold distemper of the womb’, one cure is to take galengal, cinnamon. nutmeg, mace, cloves, each two drachms; ginger, cubebs, nedory, cardamom, each an ounce; grains of paradise, long pepper, each half an ounce; beat them and put them ito six quarts of wine for eight days; then add sage, mint, balm, motherwort, of each three handfuls; let them stand eight days more, then pour off the wine, and beat the herbs and the spice, then pour off the wine again and distil them’. At least these ingredients are easier to get hold of than prepared skull! The book contains all the usual accretions, physiognomy, problems etc, but there is an additional and alarming section on venereal diseases.

This little book went blithely on its way, spawning editions, apparently until the 1930s. What appears to be a twentieth century edition (from The London Publishing Company, 223 Upper St Islington) is bound in smooth red cloth and is, I think, the “little red book” which went the rounds of my school dormitory for us smutty little boys to giggle over. No attempt whatsoever has been made to bring the contents up to date. The advice to midwives is unchanged, the only references are to Hippocrates and Galen. The herbal remedies are just as complex and the medical vocabulary just as medieval. The publishers must have known that they were producing manifest nonsense, but still it sold and, to quote W S Gilbert, there’s a grain or so of truth among the chaff.

A L Rowse in “A Cornish Childhood tells us he found a copy under his mother’s mattress; the Masterpiece also finds a mention in “Ulysses”and in “Tristram Shandy”. It has been graced with a generous amount of serious study. Sociologists, feminists and, for want of a better term, sexologists have all mined its content; missing are the bibliographers. Many editions were published in the USA, almost all are undated and a formal sequential and geographical review is long overdue.